The Florida Project

By Brian Eggert |

Far removed from the various Disney imaginariums littered throughout central Florida, the Magic Castle resides on the outskirts of Orlando. It’s a three-story motel splashed in pastel purple and cream-yellow accents, just down Seven Dwarfs Lane from unpolished monument-storefronts like the Wizard Gift Shop, with its shabby Merlin relief emanating from the storefront; the orange-colored half-sphere of Orange World; and Twistee Treat, an ice cream stand shaped like a giant cone. Just around the corner from the Magic Castle is another so-called “welfare motel” dubbed Futureworld, but the lack of an artifice covered in giant robots suggests they haven’t caught on to the branding strategy. To be sure, the Magic Castle probably looks like a storybook palace to the child characters of Sean Baker’s The Florida Project—a film whose title has a double meaning: employees at the Mouse House supposedly refer to Disney World as the “The Florida Project,” while the film’s characters inhabit a sort of underground in which motels serve as housing projects.

Baker—whose last film, Tangerine (2015), was a breakthrough about a transgender sex worker and shot entirely on iPhones—explores his subject with sensitivity, embracing the varying measures of beauty and dinginess abound. Set in the summer months in the Sunshine State, the film revolves around a talkative and beaming child named Moonie (Brooklynn Prince), who spends her days getting into trouble with her cohort Scooty (Christopher Rivera). In the opening scenes, the two children visit Futureworld and have a spitting contest, using a resident’s car as a target. Before long, Moonie’s mother Halley (Instagram celeb Bria Vinaite in her acting debut), a devout anti-authoritarian covered in rose tattoos, joins the scene to lackadaisically watch as Moonie and Scooty carry out their punishment, cleaning off the saliva-doused automobile. At least they get a new friend out of it: Jancey (Valeria Cotto), a child their age, belongs to the car’s owner.

Rambunctious and filled with relentless energy, Moonie and her friends are good kids. “…Most of the time,” says Bobby (Willem Dafoe), the Magic Castle’s manager. Playing a low-key character instead of the tortured souls he’s best known for (Jesus, the Green Goblin, etc.), Dafoe proves warm, funny, and human, with a touch of melancholy. At night, he leans over to rest his arms on the third-floor balcony and smokes a cigarette, looking into a sunset (the film contains a number of impressive sunsets, making the storybook colors of the Magic Castle even dreamier). Hints to Bobby’s past, including an estranged relationship with his son (Caleb Landry Jones), suggest the motel provides him with the same escape from despair as its residents. But the job requires him to serve in multiple roles, from accountant to bill collector, from handyman to painter, and while he might not want to admit it, he also looks out for the many children in his building. One unnerving sequence finds Bobby spotting an eerie weirdo scouting the children as they play, and he intervenes to defend the young.

The child residents of the Magic Castle find moments of incredible joy in their lives, which almost always mingle with scenes that are downright uncomfortable for the viewer. The carefree world inhabited by the children, and the formal approach of low angles to capture their perspective, is juxtaposed by the adult world of unpaid bills, mouths to feed, and threats of eviction—all captured in handheld camerawork by Alexis Zabe. One adventure follows Moonie and her friends exploring abandoned houses, clearly once the homes of squatters. Moonie spends tubby time shampooing the mane of her toy pony, while, behind a closed bathroom door and blaring tunes, her mother earns rent money in the next room. The balance of sweet and bitter is omnipresent. As one character notes, for every pile of waffles that Moonie enjoys drenched in maple syrup, there is a night of farting to follow.

Most of the film’s unpleasantness centers on Halley, Moonie’s hurricane-of-a-mother. Ever combative and desperate for cash, vague allusions to Halley’s criminal past (punctuated by the cliché line, “I can’t go back to jail”) leave a sense of unease, not to mention how most interactions with the character either descend into shouting or reveal some frightening stroke of bad parenting. Of course, Baker avoids passing judgment, but expect to audibly gasp or groan more than once in Halley’s presence. She’s an abrasive, at times monstrous, but not unsympathetic character doing what she must to provide for her child, not always in the best way. “Pepperoni costs money,” she tells Moonie as they chow down on cheese pizza. Vinaite’s unpolished performance often shows signs of her inexperience; fortunately, Baker’s direction, and our immersion into the film’s alternating adult and childlike worlds, is complete.

A champion of representing marginalized groups, Baker’s portrait of poverty settles on an observation made by many films about children, that youngsters can exist so completely in their own worlds that they remain oblivious to the adult hardships going on around them. Most of The Florida Project‘s two-hour runtime feels marked by these alternating measures of authenticity and comic mischievousness, propelled by the arrival of Prince, who gives a performance that demonstrates her talent, natural personality, and Baker’s ability to work with children. It remains unclear whether Moonie’s long tirades or stream of consciousness insights (“Forks should be made out of candy, so you can eat them after dinner”) are the results of Baker and co-writer Chris Bergoch’s script, or just Prince’s effervescent personality. In any case, they provide a much-needed tonic to the caustic, saddening presence of Vinate’s Halley.

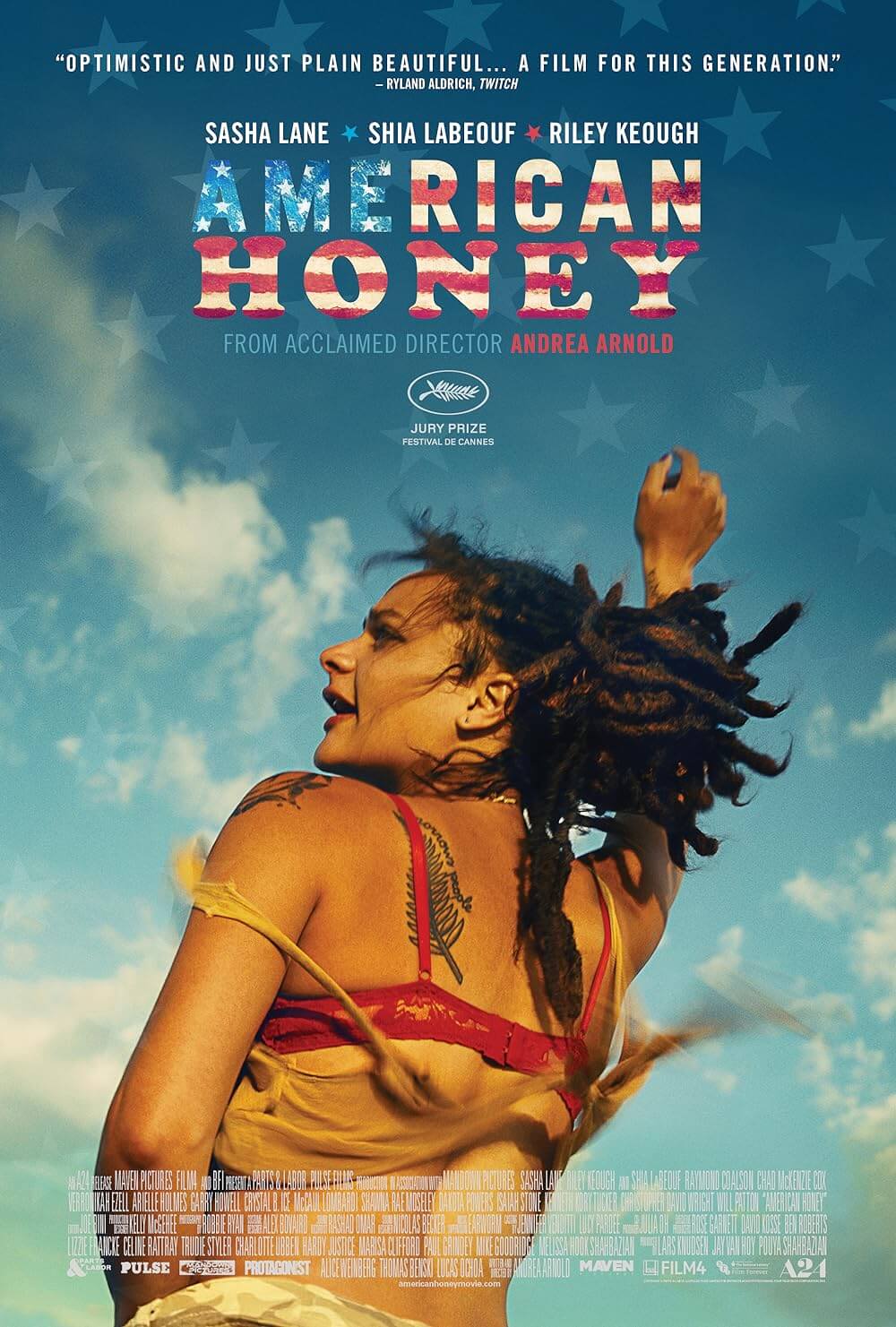

The Florida Project remains less a work of social realism than it may initially seem. Baker maintains a touch of romanticism, irony, and whimsy in his films, leading to a finale that finds itself swept away by the promise of Disney World and “Celebration” by Kool & the Gang. And while at times Baker observes the behaviors of his child actors like a documentarian might, elsewhere he gets carried away in almost Malickian, fanciful moments reminiscent of The Tree of Life (2011)—a whirling camera orbits characters as they circle each other in a blissful downpour. Baker’s approach is comparable to a more buoyant version of Andrea Arnold, whose scathing and miserable, yet oddly glorious showcases in Fish Tank (2009) and last year’s outstanding American Honey provide an unflinching look at the everyday conditions of her subjects. The charm, wrenching emotion, and compassion that Baker finds in his characters are enhanced by his unique touches of humor and unlikely optimism, making The Florida Project a bittersweet experience that, despite its faux-Magic Kingdom name, finds actual magic in the Magic Castle.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review