A Ghost Story

By Brian Eggert |

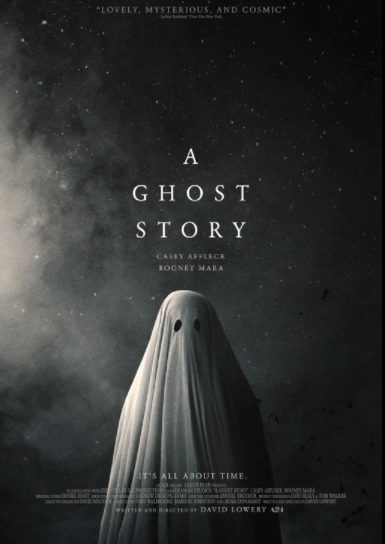

A meditation on the impermanence of material objects and human life, and the lasting consequence of love over time, A Ghost Story considers why a spirit would linger in a particular place, watching the living from beyond the grave. David Lowery wrote and directed the film as a metaphysical tale that ponders the afterlife from a ghost’s perspective. A spirit remains in his former home, drifting through time and space, watching his widowed wife and the house’s later inhabitants, reshaping our notion of what it means to be haunted. Rooney Mara plays the unnamed widow; Casey Affleck plays the ghost. But Affleck’s actual presence on screen is brief; for most of the film, his character remains under a hospital sheet like a cheap Halloween costume, albeit with vacant, black eye holes cut into the fabric. Another actor spent most of the time under the sheet. But the question is not whether we can tell if Affleck is beneath the sheet; it’s whether or not the film and its audience can overcome the silliness of the central device.

Early on, Mara and Affleck play a couple living in a shabby house in rural Texas. She wants to move, he doesn’t, and a few light flickers and odd sounds around the house at night have put her on edge. They don’t say much to one another, and not a moment is wasted on exposition or background. Having starred together in Lowery’s 2013 feature Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, the two share a wounded kind of chemistry that somehow fills the space between their characters. But before we feel any emotional connection to the couple, he dies. In the hospital, he awakens under a sheet, walks home, and proceeds to watch his widowed wife deal with the aftermath. From this moment onward, he never speaks, just watches silently; his body language beneath the sheet (pensive hanging heads, prolonged stares, etc.) provides the only hint to his state of mind; otherwise, he’s a cipher. Over the course of months, he watches her until, gradually, she moves on. Other people—a single mother and her two children, partying hipsters—move into the house, and he becomes a spectre, albeit purely out of frustration that his wife is gone. More people come and go, but soon time turns into something less linear.

More than midway through the film, the ghost watches a partying group of twentysomethings get drunk in his former house and talk about important things. In the midst of their discussion, a soapboxing hipster credited as “Prognosticator” (Will Oldham) waxes philosophical about time, space, and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony—all transient concepts, he assures. Conveniently, his speech, which goes on for several minutes, seeks to explain the events that occur throughout the rest of the film. Whatever momentum A Ghost Story had built up, it stops dead in this scene. Afterward, the ghost drifts through the fourth dimension, finds himself in the distant future, then in the distant past. He wanders through a foundation under construction that, as he moves along, develops around him into a bland business office. Several quick cuts show a pioneer family claiming a plot of land, only to be seen a moment later dead from arrows, and then decomposing into dust. This might seem strange and transportive—and engaging, and surprising—had Lowery’s Prognosticator not foretold these very ideas, and had they not already been more effectively put to use in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014).

Technically, Lowery’s minimalist effort contains several formal conceits that may challenge a viewer’s patience and understanding, while thematically his film draws from heavy sources: Andrei Tarkovsky’s use of time in cinema as a contemplative device; Terrence Malick’s poetic ruminations on spiritual transcendence, love, and the dominance of Nature over time. Shot in a 1.33:1 aspect ratio by cinematographer Andrew Droz Palermo, the frame appears with rounded corners like a 1970s photograph, the image color-corrected like a sun-drenched Instagram setting. The vintage look nonetheless conflicts with A Ghost Story‘s use of modern pop-music—specifically, the song “I Get Overwhelmed,” performed by Dark Rooms, but unconvincingly attributed to Affleck onscreen. (Affleck’s role as a ghost in a sheet is more convincing that the second or two of him lip-synching.) In any case, the film looks gorgeous, even if its visual approach feels wrongly attributed to its setting. Maybe that’s the point.

Lowery’s use of long takes extends the bounds of where a shot feels boring; he holds the image even longer, unmoving until the shot goes from boring to fascinating again. The film’s already-famous sequence involves Mara’s character sitting on her kitchen floor as she eats away her mourning in the form of an entire pie. In a five-minute unbroken shot, Mara, sniffing and unable to hold back grief stricken tears, jabs at a pie and shovels gobs into her mouth. As we watch her, we also watch the ghost watching her, until she runs to the bathroom to evacuate her stomach. Rare, complete scenes like this give us an emotional consequence to the events, whereas the shattered glass quality of the film’s remainder feels intentionally disjointed—as the ghost seems willing to endure countless years of waiting to understand his wife. Similarly, out the window, the ghost sees another like him but in flowery sheets, waiting in a house. They talk in silence and subtitles. “I’m waiting for someone,” it says. When asked who it’s waiting for, the other ghost replies, “I don’t remember.”

A Ghost Story seems to draw influence from Virginia Woolf’s short story “A Haunted House,” about ghosts who return to their former home looking for something they had hidden away in life. Affleck’s ghost sees Mara write something on a scrap of paper and hide it in a doorframe, and he spends untold amounts of time trying to get at it. What happens when he finally sees the note is just as pretentious and cutesy as many of the film’s conceits, from the glowing door that opens to him in the hospital to the bedsheet itself. Such self-aware flourishes undo the emotional potential of Lowery’s approach. He intellectualizes and contextualizes every moment that filmmakers like Malick or Tarkovsky would make the audience feel their way through, never allowing the viewer to get beyond his film’s concept. While the film proves to be an ambitious and inventive approach to the usual ghost story tropes, Lowery over-explains the more abstract ideas and underemphasizes the emotional ones, leaving his film admirable, if disappointingly empty.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review