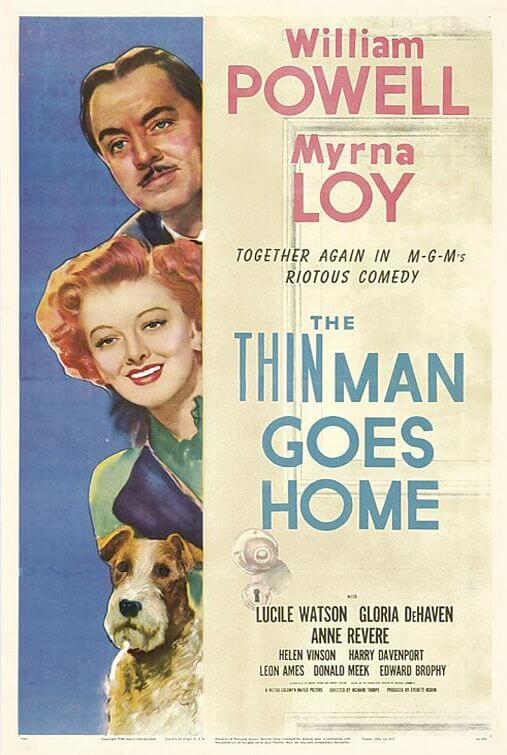

The Thin Man Goes Home

By Brian Eggert |

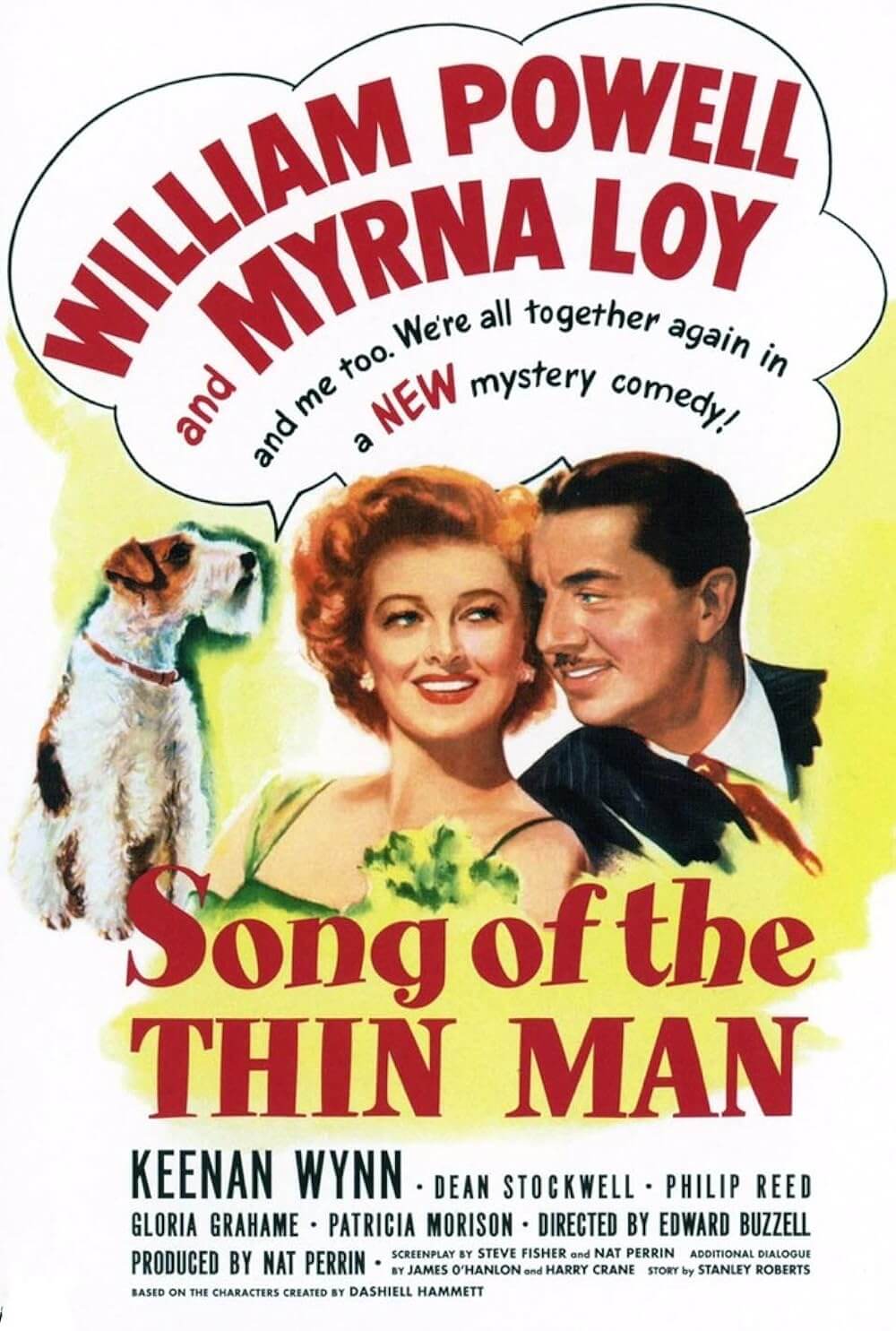

If there’s one Thin Man film that feels more out of place in the series than any other, it’s The Thin Man Goes Home from 1945. Removed from their metropolitan comfort zone and placed into a suburban neighborhood, husband-and-wife duo Nick and Nora Charles, epitomized by the incomparable screen duo William Powell and Myrna Loy, solve their fifth screen murder mystery together (with the help of Asta, too!). With the fourth sequel, the permanence of Powell and Loy’s wonderful charm in front of the camera hadn’t changed, but the main players behind the camera had been swapped out and replaced with a new producer, writer, and director to the franchise. The transition was less than smooth, and many critics and fans believed the series should have ended with this entry. The resulting film had a conspicuous shortage of the usual alcohol-imbibing antics and risqué innuendo, not to mention the sudden disappearance of the Charles’ son, Nick Jr., who was present in the previous two entries. Along with the dependable formula being reformatted in other subtle ways, some of them unsuccessful, The Thin Man Goes Home gets by as a minor, albeit pleasant sequel.

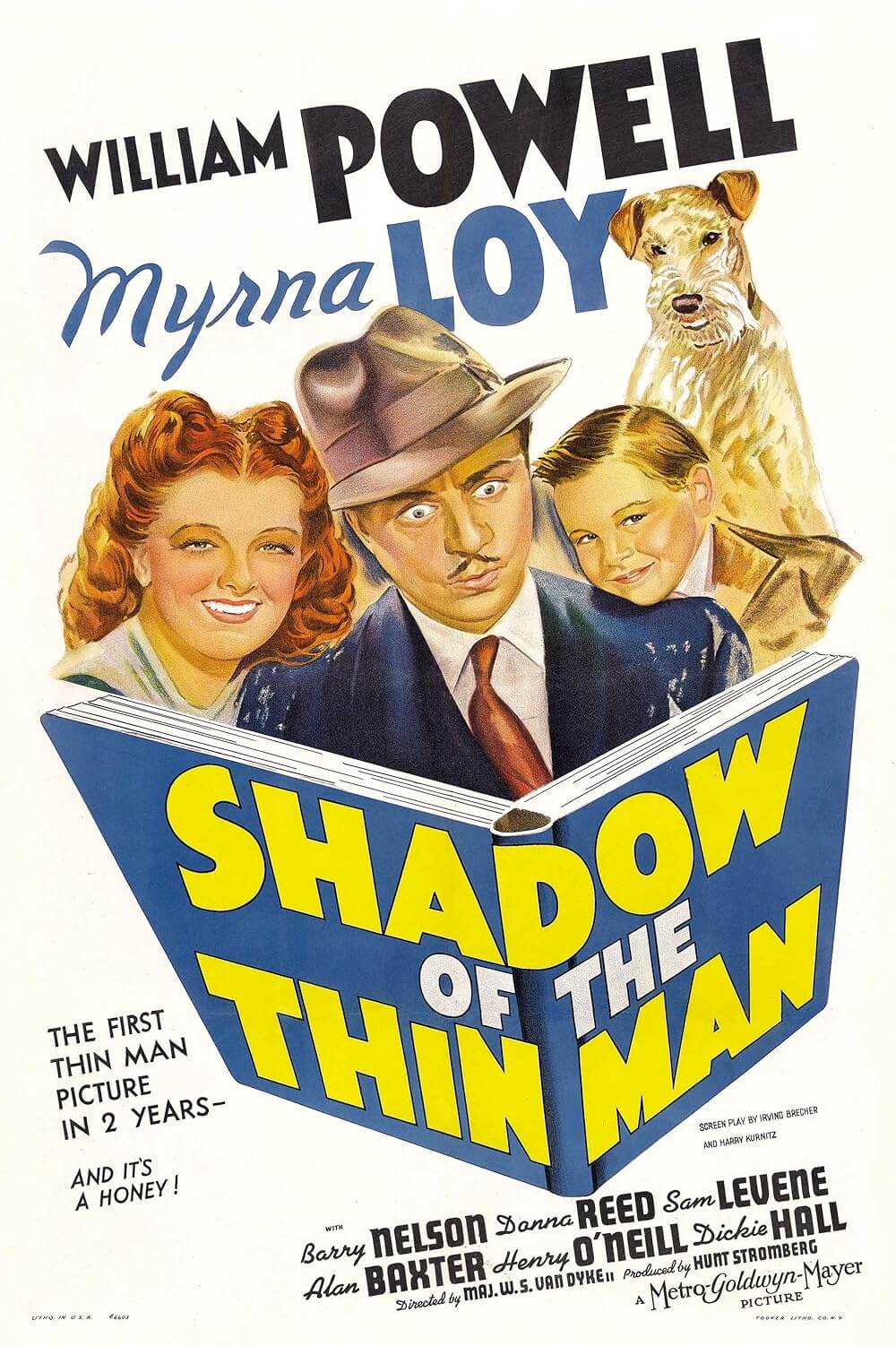

After producing 1941’s Shadow of the Thin Man, franchise producer Hunt Stromberg left MGM in 1941 to start his own independent production company through United Artists. The studio, determined to continue their bankable series, replaced Stromberg with Everett Riskin, producer of The Awful Truth (1937) and Holiday (1938), who in turn hired his brother, Robert Riskin, as the screenwriter of the fifth Thin Man film, tentatively titled The Thin Man’s Rival. Robert Riskin was famous for penning several Frank Capra pictures, such as It Happened One Night (1934) and Meet John Doe (1941), but his style was wholesome and ill-suited to the task of writing for Nick and Nora. Robert teamed with co-writer Dwight Taylor and, like many of his Capra works, set the picture in small-town America. Though the new setting was a change of pace from the series’ alternating locales of New York and San Francisco in previous films, Nick and Nora were nothing if not city slickers. The Riskins also removed alcohol from the equation, in part due to studio pressure to promote wartime sobriety, and in effect removed the high-spirited (pun intended) comic antics inherent to the series. Robert later admitted to taking the job only to appease his brother Everett, and his disconnect with the material would be evident in the final product.

In keeping with the production’s momentum as just another “studio programmer”, Richard Thorpe was assigned to direct. Thorpe made 186 films in his Hollywood tenure, most of them run-of-the-mill studio projects and B-movies. Whereas MGM positioned him to be the next W.S. Van Dyke—helmer of the first four Thin Man entries and general studio craftsman who could bring his efficient artistry to any genre, Van Dyke had died in 1943—Thorpe was a second-rate version of Van Dyke. He would deliver not one essential picture from the era, in large part due to his decided lack of personal style. But like “One Take” Woody Van Dyke, Thorpe shot fast and often used the first take, and his efficiency is why MGM liked him. James Mason, who worked for Thorpe on 1952’s The Prisoner of Zenda, once remarked, “His reputation for requiring one take is why we don’t remember his films.” To be sure, Thorpe’s films often lacked the vitality of those by Van Dyke, who orchestrated movie magic from behind the camera and captured raw, natural, unselfconsciously funny moments with his performers. Thorpe chose the first take out of budgetary and scheduling necessity, though his pictures were technically sound.

In keeping with the production’s momentum as just another “studio programmer”, Richard Thorpe was assigned to direct. Thorpe made 186 films in his Hollywood tenure, most of them run-of-the-mill studio projects and B-movies. Whereas MGM positioned him to be the next W.S. Van Dyke—helmer of the first four Thin Man entries and general studio craftsman who could bring his efficient artistry to any genre, Van Dyke had died in 1943—Thorpe was a second-rate version of Van Dyke. He would deliver not one essential picture from the era, in large part due to his decided lack of personal style. But like “One Take” Woody Van Dyke, Thorpe shot fast and often used the first take, and his efficiency is why MGM liked him. James Mason, who worked for Thorpe on 1952’s The Prisoner of Zenda, once remarked, “His reputation for requiring one take is why we don’t remember his films.” To be sure, Thorpe’s films often lacked the vitality of those by Van Dyke, who orchestrated movie magic from behind the camera and captured raw, natural, unselfconsciously funny moments with his performers. Thorpe chose the first take out of budgetary and scheduling necessity, though his pictures were technically sound.

With script development underway between Riskin and Taylor, everyone was ready to begin production except Myrna Loy. The actress who epitomized Nora Charles refused to dedicate any time to acting and instead devoted herself to her new husband John Hertz, Jr. (of Hertz Rent A Car) and her support of the war effort, particularly the Red Cross. MGM originally wanted to begin shooting the fifth Thin Man film in 1942; however, Loy made it clear she had no intention of being an actress over a wife and humanitarian. Over the next two years, the studio suspended her contract and threatened to replace her as Nora Charles. Several other actresses’ names (among them Jean Arthur, Loretta Young, Merle Oberon, Lucille Ball, and especially Irene Dunne) were hinted to the press in conjunction with unofficial discussions to recast Nora. Powell commented, “But every time such sacrilege appeared in the columns, there was an uproar. The studio was deluged with fan letters. The fans wanted Myrna… I wanted Myrna, too.” MGM’s fear tactics failed, and it wasn’t until 1944 when Loy finally surrendered and agreed to make her only film during the war years. When she arrived on the train in Pasadena from New York to begin shooting, Powell borrowed Asta for the day and met her at the station. Powell quipped, “I thought it was a hell of a nice gesture on her part to come three thousand miles to meet me.”

As a result of the studio’s pressure to get the film made no matter what, The Thin Man Goes Home feels somewhat less energetic and genuine than its predecessors. Of course, this lack of vigor and impulsiveness may be an expected result of the film’s central theme about Nick returning to his hometown, and Nora trying to convince her father-in-law that Nick has achieved a level of genius in his career as a detective, despite Nick not becoming a doctor as his father intended. In Another Thin Man, Nick hints that his relationship with his father is less than sound when Nora says her father is as honest as her husband. Nick huffs, “Some day you’ll find out what a hot recommendation that is!” In the opening scenes of this fourth sequel, Nick and Nora head to Sycamore Springs, Nick’s hometown, for seemingly no reason other than a vacation. (Nick Jr. isn’t mentioned for the first fifteen minutes or so, but it’s later explained he remained back to attend kindergarten.) The picture of small-town practicality, Nick’s unconvinced father Dr. Charles (Harry Davenport) and his quaint mother (Lucile Watson) have a comfortable home, but Nick and his father have a rocky history, as Dr. Charles has never approved of his son’s career or liberal drinking. And no matter how much Nora puts into defending her husband (her efforts make up the film’s funniest subplot), the Old Man won’t give an inch. Nora, determined to change Dr. Charles’ mind, decides to shake things up around town to see if her sleuthing husband can crack a local case during their visit.

Wholesome as it may seem, Sycamore Springs is populated by suspicious characters, all of them under Nick’s discerning eye. In a way, the plot of The Thin Man Goes Home recalls other 1940s pictures about murders that take place in an outwardly normal Everytown, USA—namely Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946). But the film doesn’t contain an ounce of cynicism toward small-town ideals in the grand thematic sense of Hitchcock and Welles’ pictures, except to suggest that murder could indeed occur in such a neighborhood. Right off the train, we meet a local loon nicknamed “Crazy Mary” (Anne Revere, excellent). Later we meet a curious young couple (Leon Ames, Helen Vinson) desperate to obtain a local painter’s work, but the artist (Ralph Brookes) is mysteriously shot—on Dr. Charles’ doorstep, no less. So, whodunit? Could it be the nervous art store proprietor (Donald Meek)? The artist’s very dramatic girlfriend (Gloria DeHaven) or her “typhoon” father (Minor Watson)? The oddball (Edward Brophy) hanging around the Charles’ bushes? The list of suspects goes on and on, and once Nick announces the killer in standard format (with everyone gathered for the denouement), his father finally grants him some approval with a smile and a pat on the back: “Great work, my boy!”

Wholesome as it may seem, Sycamore Springs is populated by suspicious characters, all of them under Nick’s discerning eye. In a way, the plot of The Thin Man Goes Home recalls other 1940s pictures about murders that take place in an outwardly normal Everytown, USA—namely Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946). But the film doesn’t contain an ounce of cynicism toward small-town ideals in the grand thematic sense of Hitchcock and Welles’ pictures, except to suggest that murder could indeed occur in such a neighborhood. Right off the train, we meet a local loon nicknamed “Crazy Mary” (Anne Revere, excellent). Later we meet a curious young couple (Leon Ames, Helen Vinson) desperate to obtain a local painter’s work, but the artist (Ralph Brookes) is mysteriously shot—on Dr. Charles’ doorstep, no less. So, whodunit? Could it be the nervous art store proprietor (Donald Meek)? The artist’s very dramatic girlfriend (Gloria DeHaven) or her “typhoon” father (Minor Watson)? The oddball (Edward Brophy) hanging around the Charles’ bushes? The list of suspects goes on and on, and once Nick announces the killer in standard format (with everyone gathered for the denouement), his father finally grants him some approval with a smile and a pat on the back: “Great work, my boy!”

Whereas previous Thin Man films incite loud belly laughs and line after line of quotable dialogue, The Thin Man Goes Home relies on modest pleasantries and chuckles to sustain our interest. Powell and Loy’s familiar and lovable onscreen presence sustains our interest while the machinations of the plot carry out in a mildly involving fashion. Powell’s comic strokes are restrained and kept under wraps to preserve his character’s noted concern to impress his father; instead of cocktails, Nick downs apple cider from a comically tall hip flask. “A couple of weeks on this cider,” says Nick, “and I’ll be a new man.” Nora replies, “I sort of like the old one.” (So do we, Nora.) Undeniably, without Nick’s occasional inebriation, a large degree of Powell’s physical performance is replaced with hilariously dry, but reserved, facial expressions, while Loy remains her delightful self. And even though The Thin Man Goes Home feels less spirited (another intended pun) than its predecessors, it’s nonetheless a capable mystery and amusing comedy made better than it might’ve been thanks to the onscreen pairing of Powell and Loy.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review