The Giver

1.5 Stars- Director

- Phillip Noyce

- Cast

- Brenton Thwaites, Jeff Bridges, Meryl Streep, Alexander Skarsgård, Katie Holmes, Taylor Swift

- Rated

- PG-13

- Runtime

- 94 min.

- Release Date

- 08/15/2014

For some of us, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) was mandatory middle school reading. Nowadays, Lois Lowry’s similarly themed young adult novel The Giver (1993) has become the dystopian text of choice for school curriculums. And while Bradbury’s text was made into a serviceable film by François Truffaut in 1966, the film of Lowry’s text is nowhere near as accomplished. Lowry’s heady exploration into the importance of shared learning and emotion in society through a muted, deeply philosophical narrative, has been exchanged for a paranoid teenage dystopia escape movie, the likes of which we’ve seen before (recently in The Hunger Games and Divergent). Producer-star Jeff Bridges and director Phillip Noyce (Salt) deliver a conceptually interesting production of modest budget and notable castmembers, but the abbreviated runtime of 94 minutes is too long concerned with perpetuating a white-knuckle thriller than embracing the thoughtful discussions of Lowry’s book. But this film review is not just the ranting of a reader devoted to the source material; those unfamiliar with the book will undoubtedly feel plagued by the story’s sense of implausibility as well.

The film opens with voiceover narration from Lowry’s protagonist, Jonas, an 18-year-old boy (played by 25-year-old Australian actor Brenton Thwaites) who introduces us to his colorless world, which, for the first third is presented in black-and-white. The film’s narrator goes on to explain all the ways in which his world is different than ours. There’s no color, art, emotion, lying, platonic relationships, bad weather, war, or expression whatsoever, as the leaders of this isolated flatland community—which, similar to many others like it apparently, rests on a plateau surrounded by clouds—have suppressed such desires through a daily injection. Chemicals inhibit people’s desires and therefore, society can function peacefully, driven by the prevailing desire for peace, safety, and above all, a “sameness” of conduct and even race. And there’s a pointed concern for “precision of language”—as a result, metaphors have disappeared (at least no one will annoyingly misuse “literally” in a figurative sense here, such as “I could literally eat a horse”). But Jonas is different; he can see subdued impressions of color.

From the outset, the film’s biggest mistake is telling us how the setting is disturbingly different from our own, without letting us discover it, piece by piece, by ourselves. Screenwriters Michael Mitnick and Robert B. Weide may have included many scenes from the book, but their treatment, and the film’s approach with a narrator who has the benefit of hindsight to guide his voiceover’s observations, remove much of the surprise and shock that would normally come with many of the story’s most potent revelations. Moreover, the writers clearly have it in mind to make this the next teen phenomenon after Twilight or The Hunger Games, and in turn, fabricate a forbidden love subplot involving Jonas and his friend Fiona (Odeya Rush). All the while, Noyce seems to forget that he’s directing a world in which emotions have been suppressed. The characters, particularly the youngsters, laugh and play and worry without inhibition. The only emotions that appear to have been curtailed are those born in their loins. Once Jonas stops taking his shots and convinces Fiona to do the same, the “stirrings” below the belt return. (Then again, Lowry’s book has Jonas experience some “stirrings” while bathing an elderly woman, which may not have translated well to the screen.)

On this world’s version of graduation day, young adults like Jonas and his peers are assigned their job in the community. But at the ceremony, Jonas is skipped over and singled out. Because of his capacity to “see beyond,” Jonas has been chosen to be “The Receiver of Memory”, a mysterious position now held by a bearded Obi-Wan Kenobi-like figure (Bridges, using his Rooster Cogburn voice, but without the Southern drawl), who, now called “The Giver”, will transfer the vast majority of human memories into Jonas. Why The Receiver is a necessary community function isn’t really made clear in the film, although Lowry’s book suggests he guides the community’s elders, headed here by a resident Big Brother figure called The Chief Elder (Meryl Streep), by offering his insight based on his knowledge of history and human memory. The community has jettisoned all history, memory, and emotion so humankind can keep functioning safely, productively, mindlessly. And so, Jonas begins his training, and his marked ability to see colors is enhanced. Soon he’s feeling all sorts of emotions and can barely contain himself.

This becomes troublesome for The Chief Elder, who carefully monitors Jonas’ progress in fear of another failure, like the one ten years ago that is alluded to throughout. Jonas’ creepy parents, his regulator mother (Katie Holmes, whose casting may have an intentional off-screen parallel), and his baby-nurturing father (Alexander Skarsgård), also show concern that their son is dancing and smiling too much, while his younger sister, Lily (Emma Tremblay), persists as a happy little girl. Meanwhile, The Giver shows Jonas the joys and horrors of humankind before The Ruin—the cataclysm that impelled this world into existence. Passing on the knowledge and wisdom that weigh on him, The Giver encourages Jonas to escape when the young student can no longer bear the strain, or accept how wrong it is for the elders to deny people the basic freedoms of emotion. Before long, the film devolves into a chase sequence, complete with Jonas outrunning The Chief Elder’s motorbike goons and flying drones. It all leads to The Giver pleading to The Chief Elder in a puts-too-fine-a-point-on-it speech about the importance of love, and Jonas’ escape leading to the return of all emotions and history to the community.

As both an adaptation and a stand-alone film, The Giver is something of a mess. The emotional performances are out of touch with what’s supposed to be an unaffected environment, but nothing about this onscreen world is detached. It’s a world whose secrets are shared within the first few scenes, whose unknowns are strewn out for us, and whose sense of discovery is nonexistent. What’s more, Noyce’s conceptual choice to gradually move from black-and-white to color is inconsistent; since the effect is meant to represent Jonas’ perspective, we’re left wondering why there are still visible colors in scenes where Jonas isn’t present. Worst of all, the filmmakers of this modestly budgeted production remove Lowry’s thought-provoking intent from a book that, for some school districts, is potent enough to be banned. But no one will be thinking about the importance of memory and pain, love and history, and their impact on society after the film is over. But no one will be banning The Giver, because it’s not controversial; it’s a fascinating story that’s been reengineered to fit an overexposed, commercially viable Hollywood formula tuned for mass consumption and mindless viewership.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2

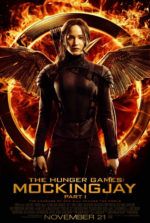

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2  The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1  The Hunger Games: Catching Fire

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire