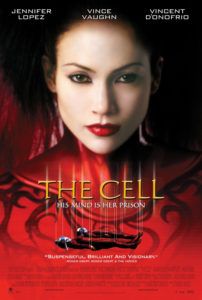

The Cell

3.5 Stars- Director

- Tarsem

- Cast

- Jennifer Lopez, Vince Vaughn, Vincent D'Onofrio, Jake Weber

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 107 min.

- Release Date

- 08/08/2000

More than just another thriller about catching a demented serial killer, more than just a trippy sci-fi odyssey into that killer’s mind, and more than just an impressive joining of genres, The Cell is a beautiful picture, which, should the viewer opt to disconnect themselves from its run-of-the-mill formula, will bring a sense of wonderment. Achieved through computer graphics and old-fashioned manipulation of the cinematic apparatus, director Tarsem (billed as Tarsem Singh, born Tarsem Dhandwar Singh) compiles unbelievable sights. Every frame is like venturing into a modern art museum comprised of nightmarish Freudian dream imagery.

Technology that allows a person to exist within the mind of another resides at the center of this film; without it, all else is standard. Scientists hoping to break new ground in psychoanalysis invent a machine that allows therapist Catherine Deane (Jennifer Lopez) to help coax a young boy out of his coma. The procedure is experimental, and over an 18-month period, Catherine has slowly gained the boy’s trust. But she still finds herself hitting walls as the mind takes all forms of bizarre and unexpected turns.

None more so than the mind of serial killer Carl Stargher (Vincent D’Onofrio), recently captured by FBI agents Peter Novak (Vince Vaughn) and Gordon Ramsey (Jake Weber). Having killed seven women victims, bleached their dead bodies to resemble dolls, and kidnapped another woman for the same treatment, Stargher remains a mystery to Novak and Ramsey. They seem to have lucked out, finding him at home, comatose from a rare neurological virus that has placed him into an inescapable coma. But where is his eighth victim? There’s no way to find out now unless Catherine takes herself inside Stargher’s mind to assemble clues.

What follows goes beyond surrealist imagery and enters into the realm of visionary. Aside from the poorly computer-drawn, pseudo-2001: A Space Odyssey tunnel Catherine falls into while entering Stargher’s mind, most of the effects are successful combinations of elaborate sets and non-intrusive CGI. In one scene inspired by British artist Damien Hirst’s installation, Some Comfort Gained From The Acceptance Of The Inherent Lies In Everything, a horse stands at the center of a well-lit room; clocks count down, and when they reach their time, sharp glass separators plunge into the animal, dividing it into several parts, all still living and beating, only split.

Costume designer Eiko Ishioka rendered the sinewy armor of the young Count in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and here, her creations are equally impressive. The suits that the doctors and patients of the psychoanalytic technology must wear are almost identical to the aforesaid armor, but Stargher’s representations, seeing himself as the colossal god of a horrendous world, ranges from twisted to terrifying and not much else in between. Long capes, his hair twisted into horns, rings clamped into his back to suspend himself, and lizard-like decorations about his body—they’re frightening and oddly stunning descriptions.

Costume designer Eiko Ishioka rendered the sinewy armor of the young Count in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and here, her creations are equally impressive. The suits that the doctors and patients of the psychoanalytic technology must wear are almost identical to the aforesaid armor, but Stargher’s representations, seeing himself as the colossal god of a horrendous world, ranges from twisted to terrifying and not much else in between. Long capes, his hair twisted into horns, rings clamped into his back to suspend himself, and lizard-like decorations about his body—they’re frightening and oddly stunning descriptions.

In his feature debut, Tarsem employs various techniques to instill every scene with its own unique appearance. His influences extend from modern artists Odd Nerdrum to H.R. Giger. His dreamworld backgrounds are washed of color or completely saturated by hues as the scene demands. Much of this comes from the case study of Stargher, designed by screenwriter Mark Protosevich. Since the killer captures his victims and encloses them in a cell, which intermittently begins to fill with water, torturing his prey, much of the resultant dream visuals are dependent on the enclosure of things. Glass boxes contain white, angel-like wraiths swimming in blue. Victims contorted with metal parts are sectioned off in display case rooms. The Stargher dream creature emerges from the water more than once, each shot at a haunting slow-motion pace.

From a narrative viewpoint, The Cell underwhelms by simply rehashing ideas explored in David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ and the Wachowskis’ The Matrix, both released in 1999. Suddenly, Catherine finds herself unable to differentiate reality from fantasy in Stargher’s mind. Later, she turns the tables when she switches the feed to bring him inside her mind, where she’s in control, clad in sexy gothic armor and wielding a warrior sword. Not much more happens aside from finding the location of that eighth victim and escaping Stargher’s deranged subconscious. Our emotional involvement goes no further than our need for Catherine to survive this ordeal.

Since 2000 when this film was released, Tarsem has only made one more picture, his self-financed 2008 masterpiece The Fall, wherein he perfects his ability to hide special effects and include the audience on a highly emotional level. We stop thinking about his methods; instead, we concentrate on the results: our complete immersion. His tales are simple, some might argue overly simple, but visuality remains the motion picture’s greatest feature. Tarsem’s dedication in that arena compares to the great painterly imaginations of Akira Kurosawa, Terry Gilliam, and Stanley Kubrick.

The Cell comes painfully close to perfection using visual stylization alone. Tarsem’s clear understanding of how to arrange his composition makes the viewer want to frame each scene and hang it on the wall. If only the plot were as complicated and rewarding as the production design. And if only Tarsem made more films, we would be privy to his (hopefully) ongoing ability to work in the confines of commercial, even pop-culture narrative limitations, while infusing them with a spectacle worthy of high art.

The Fall

The Fall  Oldboy

Oldboy  Nazi Agent

Nazi Agent