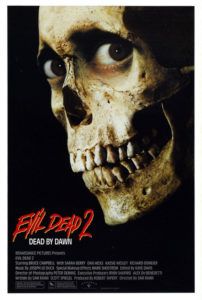

Evil Dead 2

4 Stars- Director

- Sam Raimi

- Cast

- Bruce Campbell, Sarah Berry, Dan Hicks, Kassie Wesley DePaiva, Denise Bixler, Richard Domeier, John Peakes, Lou Hancock

- Rated

- Unrated

- Runtime

- 87 min.

- Release Date

- 03/13/1987

Sam Raimi once told a crewmember that an audience must never be bored: “Whether they’re frightened, freaked out, or laughing, those are all good reactions.” In his first directorial effort, The Evil Dead (1981), Raimi managed to conjure each of these reactions by pushing horror beyond any known limits through low-budget extremes and his distinct in-your-face presentation. Audiences who weren’t screaming chuckled uncomfortably at the deliberate over-the-top violence and inherent campy quality of his independent film. When the director set out to make a sequel to his cult classic five years later in 1987, the outcome epitomized Raimi’s desire to, above all else, entertain. Evil Dead 2 one-ups its predecessor through an unrelenting string of ridiculous, bloody, and surreal off-the-wall gags, both horrific and hilarious. If the original seems exaggerated, the sequel satirizes those extremes by delivering even gorier violence with a flagrant comic edge, testing the audience’s limits. The film’s UK tagline, “Kiss your nerves goodbye” couldn’t be more accurate. More indicative of Raimi’s enduring juxtaposition of kinetic style and mordant tone than The Evil Dead, which was more an experimentation in horror style, the sequel finds Raimi looking back on his first film and realizing completely new and creative possibilities within his original vision.

Evil Dead 2 wasn’t always conceived as a horror-comedy, however. Even while making the first film, Raimi had planned to continue with a horror-swashbuckler where the hero—Bruce Campbell’s Ash—travels back to Medieval times to fight the zombie-like Deadite hordes. But after his failed second feature, Crimewave (1985), the director could not secure financing. Enter movie mogul Dino De Laurentiis, a legendary B-movie producer since the 1940s whose string of hits in the mid-1980s (including David Cronenberg’s The Dead Zone and Michael Mann’s Manhunter, both released in 1986) secured the construction of De Laurentiis’ own movie studio in North Carolina, then the largest East Coast studio of its kind (now owned by Screen Gems). De Laurentiis offered Raimi a budget of about $3.5 million to make a sequel to The Evil Dead. But rather than sending Ash back in time, De Laurentiis insisted Raimi continue his story at the isolated cabin in the woods and another round of Deadites to torment the hero—in essence, De Laurentiis wanted Raimi to remake his own film. Forced to revisit the same scenario, Raimi and co-writer Scott Spiegel opted to revamp the material. Instead of writing another straight horror film, Raimi and Spiegel fell back on their lifelong affinity for the Three Stooges to create the first ever slapstick-horror movie.

Although moments from the original film induced nervous laughter, or laughs at the occasional wooden acting, The Evil Dead’s ridiculously gory violence meant to incite laughs, even if this wasn’t the film’s overall intent. Even more than the infrequent chuckles he intended, Raimi became fully aware that audiences viewed The Evil Dead as a horror-comedy after witnessing how they responded during screenings. On the sequel, he would exploit that quality even more. Raimi resolved that if De Laurentiis wanted the same story, he would get it, but a satirical version where the director would parody what came before through a series of absurdist gags, shocks, and violence so over-the-top that an audience couldn’t help but laugh through their screams. As part of the creative overhaul, Ash too changed from a reluctant hero into a quipping badass with a chainsaw arm—a cultish figure as iconic as the era’s Snake Plissken from John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981). Campbell buffed up to become a tough-if-unlikely hero who spouts one-liners like “Groovy,” but the actor would also become a lively source of physical comedy. One of the most memorable sequences in Evil Dead 2 involves Ash battling his own possessed hand. There are no special FX in this sequence, just Campbell tossing himself about, smashing plates on his head, and contorting his evil hand into a character all its own. It remains one of the most impressive bits of physical comedy ever captured on film.

Although moments from the original film induced nervous laughter, or laughs at the occasional wooden acting, The Evil Dead’s ridiculously gory violence meant to incite laughs, even if this wasn’t the film’s overall intent. Even more than the infrequent chuckles he intended, Raimi became fully aware that audiences viewed The Evil Dead as a horror-comedy after witnessing how they responded during screenings. On the sequel, he would exploit that quality even more. Raimi resolved that if De Laurentiis wanted the same story, he would get it, but a satirical version where the director would parody what came before through a series of absurdist gags, shocks, and violence so over-the-top that an audience couldn’t help but laugh through their screams. As part of the creative overhaul, Ash too changed from a reluctant hero into a quipping badass with a chainsaw arm—a cultish figure as iconic as the era’s Snake Plissken from John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981). Campbell buffed up to become a tough-if-unlikely hero who spouts one-liners like “Groovy,” but the actor would also become a lively source of physical comedy. One of the most memorable sequences in Evil Dead 2 involves Ash battling his own possessed hand. There are no special FX in this sequence, just Campbell tossing himself about, smashing plates on his head, and contorting his evil hand into a character all its own. It remains one of the most impressive bits of physical comedy ever captured on film.

Legal issues with foreign distributors of the original meant Raimi couldn’t use footage from The Evil Dead to recap what had happened and move on. This called for Raimi to open Evil Dead 2 with a simplified retelling of the first film’s events, with a few alterations for the sake of simplicity. Gone from the original are all other characters aside from Ash and Linda (here played by Denise Bixler, since the original Linda, Betsy Baker, was unavailable). They’re alone for a romantic weekend in the isolated cabin owned by Professor Knowby, whose tape recording once again awakens ancient Deadites from their slumber. Both Ash’s hand and all of Linda become possessed, and both are summarily dismembered. At the same time, Knowby’s daughter Annie (Sarah Berry) and her preppy boyfriend Ed (Richard Domeier), escorted by local hillbillies Jake (Dan Hicks) and Bobby Joe (Kassie Wesley), trek out to her father’s cabin with missing pages from the Necronomicon, the Sumerian Book of the Dead. When they arrive, they find buckets of blood and a one-armed man raving about something evil in the woods. It doesn’t take long for everyone to realize Ash’s ravings are true, and the only way to stop the Deadite threat is to render the evil into physical form and kill it. Of course, something goes wrong, and Ash is sucked back in time to 1300 AD, where he’s expected as the hero prophesied to eliminate the Deadites—a prophecy he knows to be ill, since the Deadites still survive in his present.

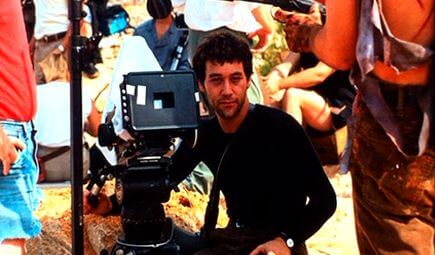

Shooting the picture, almost every sequence required some makeshift camera rigging, elaborate special effect, or inventive piece of technical innovation. Consider the Force shots—sequences filmed from the perspective of unseen Deadites. Each is more ambitious than the last. One shot pushes through the rear window of Raimi’s oft-filmed car “The Classic” and breaks the windshield to continue its chase. Another pursues Ash through every nook and cranny of the Knowby cabin, behind walls, through doors, and, hilariously, the Deadite POV eventually loses the trail only to cry out into the woods with enraged frustration. When, after 7-minutes of screentime, Evil Dead 2 finally picks up where the original left off with the Force rushing into the lone survivor Ash, the shot continues by lifting Campbell and carrying him through the woods on a constructed rig, spinning him around like he’s on a knife thrower’s wheel. By itself, Raimi’s subjective camerawork, completed by three cinematographers (the majority by Peter Deming), represents an intensely inspired combination of technical and visual flourishes. Combine his camera’s insano movements with the film’s other special FX (including blue screen work, makeup more elaborate than its predecessor, full body suits, an animated time-sucking vortex, stop-motion animation, miniature animation, the huge mechanical creations for the demon-turned-flesh in the climax, and gallons of fake blood), and one cannot help but celebrate Evil Dead 2 as one of its decade’s most impressive low-budget productions.

Shooting the picture, almost every sequence required some makeshift camera rigging, elaborate special effect, or inventive piece of technical innovation. Consider the Force shots—sequences filmed from the perspective of unseen Deadites. Each is more ambitious than the last. One shot pushes through the rear window of Raimi’s oft-filmed car “The Classic” and breaks the windshield to continue its chase. Another pursues Ash through every nook and cranny of the Knowby cabin, behind walls, through doors, and, hilariously, the Deadite POV eventually loses the trail only to cry out into the woods with enraged frustration. When, after 7-minutes of screentime, Evil Dead 2 finally picks up where the original left off with the Force rushing into the lone survivor Ash, the shot continues by lifting Campbell and carrying him through the woods on a constructed rig, spinning him around like he’s on a knife thrower’s wheel. By itself, Raimi’s subjective camerawork, completed by three cinematographers (the majority by Peter Deming), represents an intensely inspired combination of technical and visual flourishes. Combine his camera’s insano movements with the film’s other special FX (including blue screen work, makeup more elaborate than its predecessor, full body suits, an animated time-sucking vortex, stop-motion animation, miniature animation, the huge mechanical creations for the demon-turned-flesh in the climax, and gallons of fake blood), and one cannot help but celebrate Evil Dead 2 as one of its decade’s most impressive low-budget productions.

Rather than submit to what De Laurentiis Entertainment Group (DEG) expected would be an inevitable X-rating, the studio opted not to present Evil Dead 2 to the MPAA. Unrated films, after all, have their own built-in fanbase. Instead, the film opened on Friday the 13th in March of 1987 without a rating. Raimi’s sequel competed with the likes of Lethal Weapon and A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors. Box-office numbers were meager and disappointing at first, but the film soon turned a profit by earning around $6 million in receipts. A few critics caught on to Raimi’s satiric aims, although many did not. Roger Ebert keenly observed how the film “is about bad taste,” whereas other, perhaps less sophisticated reviewers merely deemed it to be in bad taste. Today, it’s almost impossible to imagine someone watching the film and somehow missing or failing to appreciate Raimi’s nonstop visual puns, Campbell’s physical humor, or the thought put into each sequence. Brilliant little asides, such as Ash trapping his rogue hand under a bucket and holding it down with a copy of A Farewell to Arms, are tangential but clever. Another sequence shows the group huddled together, terrified by the jarring sounds of the cabin, their heads moving in unison like an audience at the tennis game in Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951). At other times, Raimi’s genius takes a scary moment, such as a Deadite banging on the cabin door to get in, and extends it a few seconds too long until it becomes funny. In one scene, Ash has been taken by a Deadite spirit and bangs the door. Annie screams, holding the door shut at her back. All at once, Ash’s banging stops, but Annie keeps screaming until she realizes—oh, he’s gone.

What makes Evil Dead 2 such an unforgettable experience is that, throughout the film’s short 87-minute runtime, Raimi subjects us to a volley of horror and comedy elements, taunting us with the unexpected. Much like the original, characters turn on each other without warning. More surprising is the film’s Stooge-style humor—the number of head bonks alone is off the charts. Deadites slam their heads into trees and light bulbs, and Campbell is Raimi’s punching bag. Even more remarkable is how much time Raimi spends alone in the cabin with Ash after he’s dismembered Linda and before the other characters arrive. These are the film’s most enjoyable scenes, with Campbell demonstrating his exceptional physicality and comic performance. Ash suffers a procession of tortures, beginning when Linda’s detached head bites down on his hand. He tries to remove it by bashing her noggin into anything and everything nearby, but he’s forced to remove it with a vice. Too late, as the infection has already spread to his hand, which quickly develops a mind of its own and attacks Ash, flipping his body and breaking dishes over his head. Ash finally gets the upper hand with a chainsaw and proceeds to amputate, laughing maniacally. “That’s right! Who’s laughing now?!” he shouts irreverently, while copious amounts of blood spray back onto his face. With the hand free, Ash’s rivalry with his appendage becomes Tom and Jerry-esque, the hand scurrying behind the wall through an ostensible mouse hole, giving the “finger” and uttering unintelligible squeaks. The whole sequence is a living cartoon.

What makes Evil Dead 2 such an unforgettable experience is that, throughout the film’s short 87-minute runtime, Raimi subjects us to a volley of horror and comedy elements, taunting us with the unexpected. Much like the original, characters turn on each other without warning. More surprising is the film’s Stooge-style humor—the number of head bonks alone is off the charts. Deadites slam their heads into trees and light bulbs, and Campbell is Raimi’s punching bag. Even more remarkable is how much time Raimi spends alone in the cabin with Ash after he’s dismembered Linda and before the other characters arrive. These are the film’s most enjoyable scenes, with Campbell demonstrating his exceptional physicality and comic performance. Ash suffers a procession of tortures, beginning when Linda’s detached head bites down on his hand. He tries to remove it by bashing her noggin into anything and everything nearby, but he’s forced to remove it with a vice. Too late, as the infection has already spread to his hand, which quickly develops a mind of its own and attacks Ash, flipping his body and breaking dishes over his head. Ash finally gets the upper hand with a chainsaw and proceeds to amputate, laughing maniacally. “That’s right! Who’s laughing now?!” he shouts irreverently, while copious amounts of blood spray back onto his face. With the hand free, Ash’s rivalry with his appendage becomes Tom and Jerry-esque, the hand scurrying behind the wall through an ostensible mouse hole, giving the “finger” and uttering unintelligible squeaks. The whole sequence is a living cartoon.

Raimi has long delighted in putting Campbell through the ringer, exposing him to gruelingly difficult physical shoots if only to affectionately torture his lifelong friend. Just recently, Campbell appeared in Raimi’s Oz the Great and Powerful (2013) for a single scene where the actor receives a harsh thwack! or two upside the head. One sequence in Evil Dead 2 required dumping a fifty-gallon drum of blood (red-colored water) on Campbell; the impact released on the actor was so strong that Raimi insisted they fasten a wooden board to Campbell’s back to support his spine. But Campbell’s presence, and willingness to dedicate himself physically, enhances the film. What other actor could carry this picture as Campbell does throughout the middle sections, where Raimi refuses to grant Ash immunity from Deadite punishment? Beyond the physical, Campbell’s heightened reactions are priceless in the cabin-gone-mad scenes where inanimate objects—books, shelves, a deer mount, a grandfather clock, lamps, a rocking chair, and so on—come alive with creepy madhouse laughter. Covered in blood, less one hand, and slowly losing it, Ash joins in and the hilarity becomes both riotous and twisted. Raimi has never feared testing the limits of his favorite actor, nor has he resisted sacrificing his protagonist for effect (his 2009 hit Drag Me to Hell proves the second point as well).

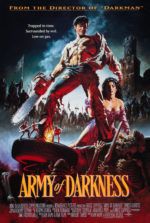

More than its predecessor, Evil Dead 2 has caused a cult sensation, largely because of its knowing, self-referential humor and outlandishly funny performance by Campbell. Just the iconic image of Ash’s chainsaw arm has been consecrated into the pop-culture consciousness, often leaving fans to unfairly overlook The Evil Dead’s merits. When I first saw the film, it was before its predecessor and just after its sequel, Army of Darkness. Once I saw all three, I couldn’t help but see Evil Dead 2 as the perfect balance between the bloody shocks of The Evil Dead and the sheer slapstick of Army of Darkness. Even Canada’s brilliant Evil Dead: The Musical (complete with “splatter zone” in the first few rows) blends this film’s comic tone and chainsaw-worn violence with the simplicity of the original’s five-college-kids-alone-in-the-woods scenario. Whereas the original finds Raimi discovering his skills with an unbelievable degree of confidence, the sequel shows Raimi’s talent and ideas refined into a pitch-perfect union of unlikely genres and styles.

More than its predecessor, Evil Dead 2 has caused a cult sensation, largely because of its knowing, self-referential humor and outlandishly funny performance by Campbell. Just the iconic image of Ash’s chainsaw arm has been consecrated into the pop-culture consciousness, often leaving fans to unfairly overlook The Evil Dead’s merits. When I first saw the film, it was before its predecessor and just after its sequel, Army of Darkness. Once I saw all three, I couldn’t help but see Evil Dead 2 as the perfect balance between the bloody shocks of The Evil Dead and the sheer slapstick of Army of Darkness. Even Canada’s brilliant Evil Dead: The Musical (complete with “splatter zone” in the first few rows) blends this film’s comic tone and chainsaw-worn violence with the simplicity of the original’s five-college-kids-alone-in-the-woods scenario. Whereas the original finds Raimi discovering his skills with an unbelievable degree of confidence, the sequel shows Raimi’s talent and ideas refined into a pitch-perfect union of unlikely genres and styles.

Seeing The Evil Dead and Evil Dead 2 one after the other, a viewer won’t detect how the former complements the latter’s narrative, or vice versa—this isn’t a progression of the story’s mythology like, for example, the development from Alien (1979) to Aliens (1986). The title’s “2” has been inappropriately assigned; these look and feel like two different films from two different universes. As a stand-alone horror-comedy, it’s an unprecedented combination of styles that inspired an entire subgenre, including titles like Tremors (1990), Shaun of the Dead (2004), and Slither (2006). Moreover, Raimi makes advances purely as a filmmaker, and his achievements in this sequel are vast, providing boundless entertainment value. We jolt and scream when possessed characters burst onto the screen without warning. Gag reflexes contract when an eyeball popped from a Deadite head flies through the air and into Bobby Joe’s mouth, the edits cutting between a mid-air trajectory shot to an eyeball-POV. Laughs arise from Campbell’s cartoonish facial expressions and impressive physical hijinks. There’s never a lull, not for a moment, always with the none-too-lofty ambition of perpetuating gory silliness on a grand scale. Evil Dead 2 is realized with such an unmatchable degree of ingenuity and energy that the film’s pure zaniness affirms its status as gloriously grotesque art.

Bibliography:

Campbell, Bruce. If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor. LA Weekly Books for St. Martin’s Press, 2001.

Muir, John Kenneth. The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2004.

The Evil Dead

The Evil Dead  Army of Darkness

Army of Darkness  Slither

Slither