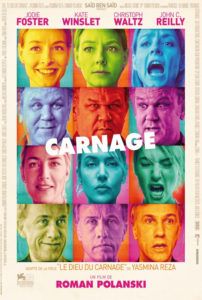

Carnage

3.5 Stars- Director

- Roman Polanski

- Cast

- Jodie Foster, Kate Winslet, John C. Reilly, Christoph Waltz

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 79 min.

- Release Date

- 12/16/2011

Roman Polanski’s best films involve confined spaces of some kind—a limited area in which the characters and thus the viewer are ensnared and cannot escape. You might call this structure Polanski’s obsession: The yacht in his first film, Knife in the Water, becomes a hotbed of jealousy and eventually murder; mysterious horrors inhabit the claustrophobic apartments in Repulsion, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Tenant; secluded houses in Cul-de-sac, Death and the Maiden, and The Ghost Writer give way to criminal goings-on. Paranoia reels through each of these close-quarter locales and they become prisons, as each example entraps a limited number of characters within a space wherein their interactions peel away the layers of their personality, revealing ugliness but ultimately the truth underneath.

With Carnage, an adaptation of the Paris-based Yasmina Reza play Le Dieu du carnage (God of Carnage), Polanski’s film proceeds in real-time and almost never leaves the boundaries of a Brooklyn apartment. Following a schoolyard incident where one 11-year-old boy strikes another in the face with a stick, the deftly smug, bourgeois parents have a civilized meeting to avoid any more serious consequences for the boys. Michael (John C. Reilly) and Penelope (Jodie Foster), the parents of the injured party, host a gathering in their home for Alan (Christoph Waltz) and Nancy (Kate Winslet), the parents of the aggressor. The two couples begin by agreeing on a written statement of what occurred, respectfully discussing the use of the words “armed with” versus “holding” a stick. Their conciliatory talks move into how the boys should apologize to one another, seep into idle chit-chat, and, fuelled by underpinnings of resentment from both sides, deteriorate into chaos as the afternoon’s dialogue exposes everyone’s hypocrisies.

The play debuted in 2006 in Zurich before appearing in France in 2008. Later that year, Christopher Hampton adapted an English-language version for the London stage. The one-act production didn’t arrive on Broadway until 2009, and originally featured James Gandolfini, Marcia Gay Hardin, Jeff Daniels, and Hope Davis; it walked away with a Tony Award for Best Play. But in Polanski’s version, he and the playwright Reza have returned to the original text and made revisions from there. For obvious reasons, Polanski couldn’t film on U.S. soil, so he shot his film in Paris. Only brief bookend moments on the playground were shot in New York by a second unit; beyond that, Polanski flawlessly evokes a New York backdrop with the use of paintings and subtle computer technology. For the interior, production designer Dean Tavoularis puts together an apartment in which Pawel Edelman’s camera moves about fluidly, making the most of his limited space without one ill-conceived shot. With a runtime of 79 minutes, Polanski keeps us rapt in a breezy, biting comedy of mounting social frustrations.

More prudish than their new acquaintances, the moneyed Alan and Nancy hope to wrap up their obligatory and uncomfortable meeting quickly; they leave their coats on and make for the door at every opportunity. Polanski taunts their escape when, going through the motions of saying goodbye, they make it into the hallway, almost into the elevator even, only to be offered a last-minute cobbler and cup of coffee. And so they go, back into the apartment of the middle-class liberal hosts who consider themselves broad-minded. Michael sells decorative hardware supplies and Penelope is a struggling writer working on a book about Darfur, and they try to remain understanding. And at first, corporate attorney Alan and investment broker Nancy seem like the guilty party, being the parents of the aggressor. Rudely, Alan keeps interrupting their conversation with incessant cell phone calls as everyone else patiently waits, while Nancy’s reserved conduct comes off as bitchy. But good manners are tested after Nancy suddenly becomes ill and projectile vomits all over the coffee table and Penelope’s rare art books. The accident peels away another layer of good manners that reveals how much Michael and Penelope have been putting on.

Just when it should end, semantic debates erupt about whose boy incited the scuffle, whose boy is a “snitch” or not, and whose approach to parenting is best. It comes out that Michael and Penelope’s child was harassing the supposed “maniac” attacker with his youth gang and perhaps provoked the incident. Add alcohol to these disagreements and inhibitions fall, mutating into arguments and shouting. Alan’s continual cell phone calls fan the flames, as does Penelope’s refusal to concede her high moral ground; Michael becomes the target of Nancy’s attack when it’s revealed he ostensibly murdered a hamster. At one moment, you might side with Michael or Penelope, but then all at once the conversation takes a turn and you find yourself siding with Alan or Nancy. Each couple attempts to support their partner, but after a few drinks, the men have moved to one side of the room and the women to the other. This escalating exchange soon finds each “civilized” individual on their own facing the meaninglessness of it all, and defending their defenseless position from three other attackers.

Although each character is exaggerated in ways best associated with compact stage production, Carnage can nonetheless be enjoyed for the superior performances on display. Foster’s transition is the most impressive, her severe politeness slowly eroding into the most vocal, high-pitched hysterics. Winslet, too, may seem demure at first, but slowly transforms into a reactionary capable of lashing out. Reilly, an underrated dramatic performer, perfectly blends his comic and dramatic styles here. Waltz’s performance is the most fascinating, giving Alan a cold-hearted façade that crumbles into a weakened figure when his cell phone takes a bath. But each of the actors accomplishes something incredible beyond bringing to life a gamut of emotions within a limited timeframe; they’re able to do this while also acting drunk. Playing drunk is one of the hardest things for an actor to accomplish realistically, especially in a comedy. Emphasize your slurs and body language too much and it’s absurd; do it too little and it’s ineffective. Not every actor could play these roles, and even fewer still could realize them in inebriated states. Yet each of them is completely convincing. Moreover, Winslet not only has to play her character drunk but also has the added challenge of drifting in and out of nausea.

Polanski’s film is fast-paced, deceptively simple, carefully arranged, and often hilarious in its observations about social decorum and the hypocrisies therein. His use of space borders on brilliant without becoming flashy or self-indulgent, and he never attempts to change the material into something pointedly cinematic. And yet, this very much feels like “a Roman Polanski film” in the best ways. Another filmmaker might have been tempted to expand the script somehow, or include scenes outside of the apartment. But Polanski is right at home in this almost single-room investigation. Some may consider this characteristic the film’s downfall, that the space and characters occupy what must be called filmed theater. But that confined nature is the trademark of Reza’s play and the exact reason why Polanski was no doubt drawn to it. With the exception of Glengarry GlenRoss, few play-to-film adaptations have so lovingly preserved the source material. And with his prestigious ensemble that seems tailored to their roles, Polanski’s craft allows them to flourish.

Non-Fiction

Non-Fiction  Thoroughbreds

Thoroughbreds  Crimes and Misdemeanors

Crimes and Misdemeanors