The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

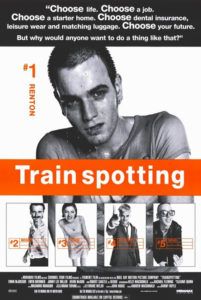

Trainspotting

- Director

- Danny Boyle

- Cast

- Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Robert Carlyle, Jonny Lee Miller, Peter Mullan, Kevin McKidd, Kelly Macdonald

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 94 min.

- Release Date

- 02/23/1996

As hobbies go, surveying trains and collecting detailed, personalized information about them resides in a unique class of lowly pastimes. And aside from train-bejeweled wallpaper, the activity has no place in Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting, except as a metaphor to explain the tedium of dreary drug habits maintained by its characters. Rather unlike its title, the film injects a vivid concoction—a brew of unfiltered drug culture cut by surprising humor, unrelenting momentum, and visual bravado dipped in surrealism—straight into our receptors. Based on Irvine Welsh’s novel from 1993, the film catapulted Boyle’s talent into the international cinematic consciousness, despite its outwardly Scottish national identity, and became an icon of 1990s counterculture. Following a group of heroin-addicted schemies, lower-class citizens living in council estates in Leigh, Edinburgh’s shabby port district, the film resists a moralized discussion of drug use to instead present a story whose ugly, darkly comic details pulse with Boyle’s kinetic touch. Through themes of addiction and friendship, watching the film becomes a sensory experience marked by the director’s signature energy.

Released in 1996, just two years after Boyle’s debut with Shallow Grave, Trainspotting gathered attention long before it appeared in theaters. Welsh’s novel was not only a national bestseller but a renowned cult piece that had already been turned into a stage play. Drawn to the author’s exploratory use of Scottish dialect on the page and range of literary conventions, as well as being a text filled with modern cultural awareness, both high- and low-brow readers made the book an immense success. Consequently, Channel Four jumped at backing John Hodge’s script and gave Boyle, the director whose first film became the U.K.’s highest grosser of 1995, a budget of $3 million. Boyle and Hodge made discerning alterations to Welsh’s book, a piece that is neither cinematic nor flowing; rather, its structure is episodic and fragmented, even disjointed by multiple voices from chapter to chapter. Hodge’s approach was to keep Welsh’s spirit but enforce a stronger narrative with a central voice, namely that of the film’s narrator and “hero” Mark Renton, played by Ewan McGregor in his breakout performance.

Renton first appears sprinting away from a botched robbery, followed by Spud (Ewen Bremner), the only other sympathetic character in their clan. Later, we meet Dave (Kevin McKidd), who dies after contracting HIV, and whose decaying goes ignored by his friends once he becomes too far gone. There is also Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), a contented self-serving pimp. And their makeshift warden is Begbie (Robert Carlyle), an impulsively violent, drug-free criminal unrestrained by fear and willing to throw down at any moment. As Renton says later, “He’s a psycho, but what can you do?” The narrative broad strokes paint a story where this clique of destructive friendships becomes a worse addiction for Renton than heroin; even after he kicks smack, he finds himself hooked on his friends and unable to cut loose. Enablers all, their association exposes him to a dangerous life he no longer wants to lead, keeping him in the rhythm of addiction when his tempo has slowed. At one point, Renton remarks that the worst part of coming off “junk” is being around his friends, who remind him who he really is. Throughout the course of the film, he begins to reject their warped sense of values and prison-like rules of loyalty.

Renton first appears sprinting away from a botched robbery, followed by Spud (Ewen Bremner), the only other sympathetic character in their clan. Later, we meet Dave (Kevin McKidd), who dies after contracting HIV, and whose decaying goes ignored by his friends once he becomes too far gone. There is also Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), a contented self-serving pimp. And their makeshift warden is Begbie (Robert Carlyle), an impulsively violent, drug-free criminal unrestrained by fear and willing to throw down at any moment. As Renton says later, “He’s a psycho, but what can you do?” The narrative broad strokes paint a story where this clique of destructive friendships becomes a worse addiction for Renton than heroin; even after he kicks smack, he finds himself hooked on his friends and unable to cut loose. Enablers all, their association exposes him to a dangerous life he no longer wants to lead, keeping him in the rhythm of addiction when his tempo has slowed. At one point, Renton remarks that the worst part of coming off “junk” is being around his friends, who remind him who he really is. Throughout the course of the film, he begins to reject their warped sense of values and prison-like rules of loyalty.

As narrator, Renton, no matter how naïve or in-the-moment he may appear within the frame, sets himself apart from other characters through the device of his voiceover. Having already learned the lessons within the film’s story, he looks back much wiser and more self-aware, and so if his character onscreen seems contrary to the narrator’s perspective, we must remember Renton is telling the story with a sense of reflection—after he has escaped with a bag of stolen drug money in the last scene, out to start a new life. His onscreen hedonism (even more evident in his friends) is interrupted by his unique moments of thoughtfulness, sensitivity, and reflection through narration. His story may be myopic as a result, but his tone and acerbic observations refuse to romanticize drug addiction and bring purpose to the film’s grimy subject matter. Eliminate the vitality with which Renton tells his story, and it might be reduced to a typical downer tale of drugs and debauchery, something more akin to Permanent Midnight or even Requiem for a Dream.

But the film’s treatment of addiction contains no direct censures or endorsements, its morality all but nonexistent for a realistic representation. This is not to suggest Trainspotting is “realistic” per se, just that its perspective is not a judgmental one. Boyle’s cast took a two-week training course with former addicts, learning how to cook heroin and hearing stories of first-hand experience. In the film, Renton describes its orgasmic quality in vibrant detail; the audience is made aware first of its euphoric effects, and in turn, we understand why it becomes so difficult to quit. Renton and his group appear in ironic “heroin chic,” the term coined to describe those ‘90s-era Calvin Klein models with unfocused eyes and degenerated, sickly thin physiques. More than just heroin, however, the film comments on the chemical dependency of all society—be it illegal drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, headache pills, etc. Renton acknowledges that his mother is a Valium addict, but that her socially acceptable addiction goes without concern. Given the characters’ appearance and its treatment of drug addiction, the film accepts responsibility for choosing heroin as a pop-culture alternative by describing—as opposed to venerating—addiction itself.

Renton’s descriptions of heroin usage and its effects are frank and honest, unconcerned with the moral implications of his confession, and capable of horrifying us one moment and making us laugh the very next. So often, British cinema is associated with social realism from filmmakers like Lynne Ramsay (Ratcatcher) and Andrea Arnold (Fish Tank), but Boyle embraces “black magic realism” in full regard of Britain’s tradition of surrealist, grotesque humor worthy of Monty Python. Most viewers will never forget the baby that dies of neglect because one of Renton’s female friends goes on a smack binge; it reappears in Renton’s withdrawal hallucinations, crawling on the ceiling toward him, closer and closer still. Another scene shows Renton leap from a brick wall and inexplicably land in the den of Mother Superior (Peter Mullan), their dealer. A key, gag-inducing scene for many remains the one in “The Worst Toilet in Scotland,” where Renton, stricken with abrupt post-high constipation relief, loses a curative suppository in a rancid toilet bowl. He reaches in with his hand to scoop it out but finds himself compelled to dive in and finds himself swimming in crystal blue waters, only to recover his suppository and climb out of the toilet. Another scatological-oriented scene involves Spud inadvertently spraying filthy bedsheets on his girlfriend’s family during their breakfast. Trainspotting employs a pure definition of surreality by accentuating reality with dreamlike, grotesque, or over-the-top imagery. Moments that would typically be disturbing become strangely funny, lightened by the inspirited dynamism of visual and aural embellishments that pump with the impetus of drug-addicted motivation.

Renton’s descriptions of heroin usage and its effects are frank and honest, unconcerned with the moral implications of his confession, and capable of horrifying us one moment and making us laugh the very next. So often, British cinema is associated with social realism from filmmakers like Lynne Ramsay (Ratcatcher) and Andrea Arnold (Fish Tank), but Boyle embraces “black magic realism” in full regard of Britain’s tradition of surrealist, grotesque humor worthy of Monty Python. Most viewers will never forget the baby that dies of neglect because one of Renton’s female friends goes on a smack binge; it reappears in Renton’s withdrawal hallucinations, crawling on the ceiling toward him, closer and closer still. Another scene shows Renton leap from a brick wall and inexplicably land in the den of Mother Superior (Peter Mullan), their dealer. A key, gag-inducing scene for many remains the one in “The Worst Toilet in Scotland,” where Renton, stricken with abrupt post-high constipation relief, loses a curative suppository in a rancid toilet bowl. He reaches in with his hand to scoop it out but finds himself compelled to dive in and finds himself swimming in crystal blue waters, only to recover his suppository and climb out of the toilet. Another scatological-oriented scene involves Spud inadvertently spraying filthy bedsheets on his girlfriend’s family during their breakfast. Trainspotting employs a pure definition of surreality by accentuating reality with dreamlike, grotesque, or over-the-top imagery. Moments that would typically be disturbing become strangely funny, lightened by the inspirited dynamism of visual and aural embellishments that pump with the impetus of drug-addicted motivation.

No matter how well the grim material may be “lightened” by the humor when recalling the film’s soiled details, one must recognize—and even meet with open arms—the film’s usage of sensory pleasure (or loathing) and moral obliviousness. In Renton’s opening diatribe, at the end of one of his many lists, he declares, “Choose your future. Choose life… But why would I want to do a thing like that? I chose not to choose life. I chose somethin’ else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin?” Already, Renton acknowledges that for his group of friends, life means the pursuit of heroin, which he realizes is no kind of life at all, but it is also one he cannot escape. All the more inspired, then, is Boyle’s use of “Lust for Life” behind the voiceover. Iggy Pop’s raunchy song goes on about the association between filth and pleasure (“Well I am just a modern guy/Of course I’ve had it in the ear before/‘Cause of a lust for life”). Tonally, the film emulates the song with an ironic enthusiasm behind its unpleasant, sometimes downright sickening details. In this sense, Trainspotting is a film about the fetishization of misery through heroin, versus ‘a film about drugs,’ such as Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic, which follows the drug from production to distribution.

Along with Renton’s near-continuous voiceover, Boyle’s highly stylized formal approach coagulates the material into a living, breathing organism, always moving, and ever dynamic. Boyle’s presence is stylized, but never pretentious or blatantly artistic, employing technical tricks that reinforce the potency of the story rather than stand out on their own. Mirroring a shot from within a water bottle in his 2010 film 127 Hours, Boyle takes us inside a syringe as brown fluid (not unlike the toilet water from “the worst toilet in Scotland”) drains into Renton’s vein. Imaginative shots like this, along with cinematographer Brian Tufano’s utilization of fish-eye lenses and creative angles to transport the audience into a borderline hallucinatory state, establish an unreality to the film’s chaotic world. The film itself is structured by concurrent stories linked through space and time through editing. In one sequence, Boyle cuts between Renton, Spud, and Tommy as they attempt to realize their respective sexual conquests, while New Wave rocker Blondie’s wonderfully suggestive “Atomic” provides the beat. Masahiro Hirakubo’s editing connects multiple stories for an intrinsic understanding through montage, as opposed to cohesive, step-by-step cutting. And the speed at which such sequences are cut brought the original 2-hour-and-20-minute length to a brisk 94-minute runtime.

Fast, economical, and spotless cuts establish movement, whereas sudden freeze-frames emphasize movement even more with an abrupt break in forward motion. Enhanced by the marriage of story, narration, and music, the almost continuous pulse throughout suggests the momentum of addiction, a pace set by music and editing, and a pace from which Renton cannot break free. He describes addicts as always searching for their next score, robbing anyone and everyone, delving into the lowest of lows to find cash to cook up. And so, rarely are there scenes without multi-sensory layering, a flurry of stimuli to drench the brain. Boyle lays down narrative with music, narrative with narration, or often all three (narrative, music, narration). Only in a few scenes does the narration and music drop out and allow the story to stand on its own. As if shocked into sobriety, the characters escape their rigorous drug tempo during severe, dramatic moments: when Renton pays Tommy a visit after learning of Tommy’s HIV; when Spud sings “Two Little Boys” after Tommy’s funeral at the pub; after Renton and Spud’s trial, where they meet at the same pub, to lament that Spud went to prison. Meanwhile, the soundtrack contains counterculture songs—with ‘70s rocks icons like Iggy Pop and Lou Reed; ‘90s Britpop like Blur, Elastica, and Pulp; and ’90s techno from Bedrock and Ice MC—playing to several generations of viewers, spanning them just as the film’s values do.

Fast, economical, and spotless cuts establish movement, whereas sudden freeze-frames emphasize movement even more with an abrupt break in forward motion. Enhanced by the marriage of story, narration, and music, the almost continuous pulse throughout suggests the momentum of addiction, a pace set by music and editing, and a pace from which Renton cannot break free. He describes addicts as always searching for their next score, robbing anyone and everyone, delving into the lowest of lows to find cash to cook up. And so, rarely are there scenes without multi-sensory layering, a flurry of stimuli to drench the brain. Boyle lays down narrative with music, narrative with narration, or often all three (narrative, music, narration). Only in a few scenes does the narration and music drop out and allow the story to stand on its own. As if shocked into sobriety, the characters escape their rigorous drug tempo during severe, dramatic moments: when Renton pays Tommy a visit after learning of Tommy’s HIV; when Spud sings “Two Little Boys” after Tommy’s funeral at the pub; after Renton and Spud’s trial, where they meet at the same pub, to lament that Spud went to prison. Meanwhile, the soundtrack contains counterculture songs—with ‘70s rocks icons like Iggy Pop and Lou Reed; ‘90s Britpop like Blur, Elastica, and Pulp; and ’90s techno from Bedrock and Ice MC—playing to several generations of viewers, spanning them just as the film’s values do.

Boyle’s use of music and film culture in a nationalized context helped expand the film’s range, most obviously with the American-inspired soundtrack. From Iggy Pop to Hollywood movies, the presence and influence of American culture is felt, and thus easily consumed by U.S. audiences—Sick Boy continuously talks about James Bond (Hollywood productions regardless of the Scottish star Sean Connery); Begbie fancies himself to be Paul Newman in The Hustler; Renton reads a biography on Montgomery Clift. Boyle cited Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, Friedkin’s The Exorcist, and Scorsese’s Goodfellas and Mean Streets as direct influences during pre-production. Such evidence denotes the Americanization of Scottish and British cultures and the acceptance of Scottish and British cultures into the American consciousness. Yet, the film is a nationalized release whose regional specificities may be lost outside of the U.K.; before and possibly even after Trainspotting, doubtful that anyone knows what trainspotting is, not to mention the basics of Scottish national identity. Renton bewails, “It’s shite being Scottish! We’re the lowest of the low. The scum of the fucking Earth! The most wretched, miserable, servile, pathetic trash that was ever shat into civilization. Some hate the English. I don’t. They’re just wankers. We, on the other hand, are colonized by wankers.” This nationalistic jibe can be identified later when Renton first escapes to London, and Boyle shows off typical touristy attractions with the sardonic enthusiasm of a travel agent brochure.

Trainspotting would go on to make $11 million in the U.K., $16.5 million in the U.S., and $72 million worldwide, making it outrageously popular and successful. Youths linked the experience to clubbing or raves in the 1990s counterculture scene—Boyle’s club is so loud, subtitles are required to understand dialogue—and therefore, it was perceived as equally dangerous while also earning admiration from critics and arthouse audiences. It received wildly enthusiastic responses, some deeming it mere popular entertainment and others praising it as a significant artistic achievement—a cinematic British Invasion likened to The Beatles in the 1960s. Indeed, this is a “pop film” not unlike Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (another film marked by heroin), filled with visual cues and pop-culture references. Among the most controversial was a nod to the Abbey Road album cover, associating the film’s schemies with a hip rock group. Accordingly, Renton’s appeal is not unlike that of John Lennon amid the three other Beatles; he stands out because he is both “good” and “cool,” but at the same time, he is “bad,” with streaks of rebellion and all-out criminality. In the end, he tells us that he abandons his friends to become “just like you”—and nothing could be more boring, except he has done so by stealing a bag of drug money. Audiences could not help but connect with the material, regardless if they were Scottish heroin addicts or not; its cultural feelers extend too far to resist.

Like many British directors before him, Boyle flocked to Hollywood after Trainspotting’s success and found himself inundated with offers. For a follow-up, he chose A Life Less Ordinary (1997), a bizarre and ultimately ineffective romantic comedy about two angels who help a kidnapper and his hostage fall in love. Next came The Beach (2000), starring Leonardo DiCaprio as a traveler looking for an idyllic paradise. Both films received accusations of Boyle’s overt Americanization and commercialization, and both bombed, leading to Boyle’s veritable deportation by Hollywood. After their failure, Boyle realized his tendencies gravitated toward smaller, homespun, regional-centric films. Taking a two-year hiatus from filmmaking to direct TV movies, he returned in 2002 with 28 Days Later, the genre masterwork which reinvented zombie horror and ushered in a new resurgence of film about the walking (and running) dead. Smaller gems followed, such as Millions (2004), an adorable film about a boy who finds a bag of cash and uses it to do good. Next was Sunshine (2007), an underseen, glorious science-fiction tale about a fateful voyage into the Sun. But Boyle’s directorial magnetism would not have the same widespread draw as Trainspotting until 2008’s Slumdog Millionaire, a joyous, universal story that seemed to unite the world, as well as Oscar voters, in its unanimous praise. Now an Academy Award winner, Boyle’s status as a high-profile yet dynamic director of award-worthy titles continued in 2010 with 127 Hours.

Throughout his career, Boyle’s energy occupies every picture. More than any degree of cultural density, contrasting emotions, or social commentary embedded into the narrative of Trainspotting, the director’s aesthetic inventiveness retains the film’s status as a modern classic, and that energy is why we keep returning to this fascinating film. With great stylistic ostentation, Boyle resists trivializing a squalid world not often depicted through superficiality, although sometimes the film is misinterpreted as such. By delivering an emotionally complex tale distinct for its intertextual presentation, he creates a multifaceted experience with more to offer than surface value. Heroin-doused bleakness and wretched truths about dependence are redeemed by Boyle’s cinematic attitude, an enthusiasm unique to film, providing a strange and engaging relationship between the narrative and its treatment. His energy liberates potentially limited subject matter, isolated by its regional idiosyncrasies and desperate conditions, by speaking in a cinematic language that transcends borders to reach a larger audience. Never more evident than here, Boyle’s is an authentic voice in modern film, whose honesty and vitality bring life into the most unlikely of places.

Bibliography:

Page, Edwin. Ordinary Heroes: The Films of Danny Boyle. London: Empiricus Books, 2010.

Raphael, Amy. Danny Boyle: In His Own Words. London: Faber & Faber, 2010.

Smith, Murray. Trainspotting. British Film Institute Modern Classics, BFI Publishing, 2008.

T2 Trainspotting

T2 Trainspotting  Sunset Blvd.

Sunset Blvd.  Inside Llewyn Davis

Inside Llewyn Davis