The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

- Director

- John Huston

- Cast

- Humphrey Bogart, Walter Huston, Tim Holt, Bruce Bennett, Barton MacLane, Arturo Soto Rangel

- Rated

- Unrated

- Runtime

- 126 min.

- Release Date

- 01/24/1948

John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, an adventure about gold prospectors in Mexico, voyages into dark places where greed corrupts men and leaves them overcome by suspicion and paranoia, and even murder. Huston’s film does not dwell on a moral commentary, however; he prefers to examine individuals, watching as gold’s promise of wealth and power erodes under the pressure of desire and temptation. Vile selfishness and cruelty reside beneath the surface of Huston’s unpredictable characters. In that sense, his 1948 picture is very much about his actors and their ability to capture the debauched lows of their characters. Humphrey Bogart, Tim Holt, and the director’s father Walter Huston portray men who sink to startling depths, and yet they have rare if infrequent moments of nobility. Unlike most studio releases of the era, the film’s depiction of wretched moral depravity is not sweetened by a studio ending, where, say, the ugly impulses of greed are suppressed by a higher moral calling. Instead, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre resolves a more Hemingwayan conclusion, containing a kind of stoic acceptance and optimism by the final scenes. The allure of gold and its resulting obsessions remain a test of a man’s character in the harsh, unforgiving, and godless natural world.

John Huston was born in 1906 and lived an adventurous life both before his arrival in Hollywood and afterward. He was the only child of journalist Rhea Gore and Walter Huston, star of the screen and vaudeville stage. After his parents had divorced when he was six, he spent most of his childhood in boarding schools or traveling wherever his father’s work took them. At various times in his young life, he had aspirations to become an actor like his father, he went to school to become a painter, he also took up boxing and won the Amateur Lightweight Boxing Championship in California. Huston had a cosmopolitan life, traveling wherever his impulses at the moment took him. He studied acting in 1924 with the Provincetown Players in Greenwich Village, but then he also enjoyed riding horseback and sought out a famed trainer in the Mexican cavalry to ride with their army. In 1929, the nomadic Huston published his first short story called “Fool” in American Mercury magazine, and then set his sights on becoming a journalist. However, Huston didn’t have the requisite knack for facts; instead, he took to writing plays, a vocation that most playwrights of the era discovered led directly to Hollywood. Sure enough, Huston went under contract as screenwriter for Samuel Goldwyn. But after he went six months with no assignments, he turned to Universal Studios, where he penned screenplays for Murders in the Rue Morgue, Law and Order, and A House Divided, all in 1932. The latter picture even starred his father.

In the coming years, John Huston moved to Warner Bros. and earned Academy Award nominations for his screenplays Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet (1940) and Sergeant York (1941). At the same time, he earned a lusty reputation for hard-drinking hedonism. Nevertheless, he remained productive and his films profitable, and he wanted to direct. He arranged with Warner Bros. that if his next screenplay for High Sierra (1941), a Raoul Walsh picture starring up-and-comer Humphrey Bogart, were a hit, then he would be allowed to direct his next picture and have his pick of source material. Of course, Huston’s deal paid off, and for his directorial debut, he chose to adapt Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 detective thriller, The Maltese Falcon. Although the studio had adapted Hammett’s book twice before to unremarkable effect, Huston’s treatment remained close to the source material and featured a cast of skilled actors (Bogart, Peter Lorre, Mary Astor, Sydney Greenstreet). By the time Huston completed his fourth directorial effort for Warner Bros., World War II had reshaped Hollywood drives and, like many of his contemporaries such as John Ford, the director made wartime documentaries. Many were considered controversial and were banned for openly acknowledging issues of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or U.S. intelligence failures that resulted in major casualties. His first postwar narrative film would be The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

In the coming years, John Huston moved to Warner Bros. and earned Academy Award nominations for his screenplays Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet (1940) and Sergeant York (1941). At the same time, he earned a lusty reputation for hard-drinking hedonism. Nevertheless, he remained productive and his films profitable, and he wanted to direct. He arranged with Warner Bros. that if his next screenplay for High Sierra (1941), a Raoul Walsh picture starring up-and-comer Humphrey Bogart, were a hit, then he would be allowed to direct his next picture and have his pick of source material. Of course, Huston’s deal paid off, and for his directorial debut, he chose to adapt Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 detective thriller, The Maltese Falcon. Although the studio had adapted Hammett’s book twice before to unremarkable effect, Huston’s treatment remained close to the source material and featured a cast of skilled actors (Bogart, Peter Lorre, Mary Astor, Sydney Greenstreet). By the time Huston completed his fourth directorial effort for Warner Bros., World War II had reshaped Hollywood drives and, like many of his contemporaries such as John Ford, the director made wartime documentaries. Many were considered controversial and were banned for openly acknowledging issues of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or U.S. intelligence failures that resulted in major casualties. His first postwar narrative film would be The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

None of the films from Huston’s entire body of work compare to the virtuosity on display here. The director first read B. Travern’s 1935 book a year after it was published, and it reminded him of his time in the Mexican cavalry. Warner Bros. already owned the rights, and the studio’s plans to develop the picture during World War II had fallen through. Huston saw the challenge as twofold. First, Travern’s text does not lend itself to realism; the director compared the author’s style to a combination of Joseph Conrad and Theodore Dreiser, “if you can imagine such a thing,” he told interviewer Philip K. Scheuer. To be sure, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre delved into the hearts of darkness of its characters, but the book also contains a mannerist style of dialogue to reflect Dreiser’s heavy prose. Rather than rewrite the dialogue in more familiar, audience-friendly terms, Huston preserved much of the author’s original dialogue and relied on his actors’ delivery to sound natural. For his star, Huston reteamed with Bogart, his most frequent collaborator and leading man, as the despicable beggar Fred C. Dobbs. For the story’s other drifter, Huston hired Tim Holt, who appeared as an Earp brother alongside Henry Fonda in John Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946). And as the wise old codger who knows “what gold does to men’s souls,” the director teamed with his father, Walter Huston.

At the outset, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre remains unique for a Golden Age studio picture, since much of the production shot on location around San José de Purua, just over 100 miles north of Mexico City. Over the years, Huston exchanged letters with Travern, who lived in Mexico, about adapting the book. In 1946, after Huston wrote Travern about finally shooting his film version, the author replied with a twenty-five-page memorandum containing suggestions on how the film should be shot. When Huston asked to meet the author, a thin, graying man claiming to be Travern’s assistant and official representative, named H. Croves, greeted him. In fact, Croves was an alter ego Travern used to cover-up his own apparently debilitating shyness. Huston suspected as much (and, in 1976, Travern’s wife confirmed Croves was indeed Travern), but he hired Croves as a technical advisor for the remainder of the shoot nonetheless. Incognito or not, the author’s presence did not prevent Huston from altering the original text from a narrative with a deep-rooted subtextual denouncement of the proletariat concerns of Bolshevism and even Catholicism, and focused instead on the book’s harsh cautionary tale about knowing the land and job, being prepared, accepting fate—if fate exists at all. Huston’s biographer Stuart Kaminsky put it best when he wrote, “In a sense, Travern’s novel can be read as a Kafka-like allegory while Huston’s film version more closely resembles a film by Ernest Hemingway.”

At the outset, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre remains unique for a Golden Age studio picture, since much of the production shot on location around San José de Purua, just over 100 miles north of Mexico City. Over the years, Huston exchanged letters with Travern, who lived in Mexico, about adapting the book. In 1946, after Huston wrote Travern about finally shooting his film version, the author replied with a twenty-five-page memorandum containing suggestions on how the film should be shot. When Huston asked to meet the author, a thin, graying man claiming to be Travern’s assistant and official representative, named H. Croves, greeted him. In fact, Croves was an alter ego Travern used to cover-up his own apparently debilitating shyness. Huston suspected as much (and, in 1976, Travern’s wife confirmed Croves was indeed Travern), but he hired Croves as a technical advisor for the remainder of the shoot nonetheless. Incognito or not, the author’s presence did not prevent Huston from altering the original text from a narrative with a deep-rooted subtextual denouncement of the proletariat concerns of Bolshevism and even Catholicism, and focused instead on the book’s harsh cautionary tale about knowing the land and job, being prepared, accepting fate—if fate exists at all. Huston’s biographer Stuart Kaminsky put it best when he wrote, “In a sense, Travern’s novel can be read as a Kafka-like allegory while Huston’s film version more closely resembles a film by Ernest Hemingway.”

A pathetic vagabond scouring Tampico in 1925, Fred C. Dobbs (Bogart) has no apparent past and no certain future. He asks for handouts (“Say, buddy. Will you stake a fellow American to a meal?”), plays the numbers, picks up half-smoked cigarette butts from the ground, and believes in getting rich quick and spending his earnings even quicker. After trying everything to make his fortune, his next attempt will be no different. Along with a fellow drifter from the states, Bob Curtin (Tim Holt), Dobbs takes a job toiling in the hot sun for a crooked employer, Pat McCormick (Barton MacLane), who tries to skip town instead of paying his workers. When Dobbs and Curtin corner him about their pay, the ensuing bar fight illustrates just how pathetic Huston’s characters are. They deliver one ineffectual blow after another to McCormick, who is by no means an impressive physical specimen; and yet, our heroes are so feeble that it takes them both to punch out McCormick. With money in hand and good reason to leave Tampico behind, they look up Howard (Walter Huston), an old man who—earlier at the Hotel Oso Negro, a shelter comprised of beds in a large, filthy room—talked about his days as a prospector. Howard agrees to show them how to prospect for gold, and Dobbs agrees to be equal partners with Curtin. They shake on it, and the camera moves in on Howard’s face between them, showing uncertainty and skepticism over a partnership between two weak men.

After all, as Howard warns them, gold acts like a disease that eats away at the brain and drives a man crazy. Dobbs argues, “Gold doesn’t carry any kind of curse… All depends on if the guy who finds it is the right guy.” Dobbs and Curtin believe they can handle greed and temptation; they can handle anything, or so they believe. Once on their journey to areas far away from any village or train track, all three men show their true nature. Dobbs complains endlessly, trying to justify his laziness during the long haul. “If there was gold in those mountains, how long would it have been there? Millions and millions of years, wouldn’t it? What’s our hurry? Couple a days more or less ain’t gonna make any difference.” Curtin hangs back with Dobbs, exhausted. Howard, meanwhile, can walk all day without water and still have the energy to play the harmonica after gobbling down a plate of beans. All at once, Dobbs and Curtin think they’ve found it—gold—and as they splash water on some rocks to see glimmering veins clearly, they yell for Howard, who rushes down from atop a nearby peak to see. “Fool’s gold,” he tells them, then adds, “Next time, call me before you start spreadin’ water around. Water’s precious. Sometimes maybe more precious than gold.” Our would-be heroes are once again shown to be ignorant, weak, and out of their element. When they finally settle on some real gold, Dobbs and Curtin don’t even notice. Howard laughs like a madman, “Let me tell you something, my two fine bedfellows, you’re so dumb. There’s nothin’ to compare ya with—you’re dumber than the dumbest jackass. Look at each other, will ya? Did you ever see anything like yourself for being dumb specimens? You’re so dumb, you don’t even see the riches you’re treadin’ on with your own feet!”

After all, as Howard warns them, gold acts like a disease that eats away at the brain and drives a man crazy. Dobbs argues, “Gold doesn’t carry any kind of curse… All depends on if the guy who finds it is the right guy.” Dobbs and Curtin believe they can handle greed and temptation; they can handle anything, or so they believe. Once on their journey to areas far away from any village or train track, all three men show their true nature. Dobbs complains endlessly, trying to justify his laziness during the long haul. “If there was gold in those mountains, how long would it have been there? Millions and millions of years, wouldn’t it? What’s our hurry? Couple a days more or less ain’t gonna make any difference.” Curtin hangs back with Dobbs, exhausted. Howard, meanwhile, can walk all day without water and still have the energy to play the harmonica after gobbling down a plate of beans. All at once, Dobbs and Curtin think they’ve found it—gold—and as they splash water on some rocks to see glimmering veins clearly, they yell for Howard, who rushes down from atop a nearby peak to see. “Fool’s gold,” he tells them, then adds, “Next time, call me before you start spreadin’ water around. Water’s precious. Sometimes maybe more precious than gold.” Our would-be heroes are once again shown to be ignorant, weak, and out of their element. When they finally settle on some real gold, Dobbs and Curtin don’t even notice. Howard laughs like a madman, “Let me tell you something, my two fine bedfellows, you’re so dumb. There’s nothin’ to compare ya with—you’re dumber than the dumbest jackass. Look at each other, will ya? Did you ever see anything like yourself for being dumb specimens? You’re so dumb, you don’t even see the riches you’re treadin’ on with your own feet!”

The scenes where Howard and his two “dumb” cohorts establish a mine in the nearby mountain were all shot on location. Jack Warner greenlit the proposed ten-week location shoot without having read the script; he assumed the picture was another modestly budgeted Western programmer. Huston did little to clarify Warner’s assumptions. When the studio head watched the production’s dailies and began to receive reports of Huston’s expenditures, he realized his initial impressions were wrong. He was furious. “They’re looking for gold all right—mine!” he told producer Henry Blanke. To be sure, Huston did not cut corners to save the studio money; he demanded a certain degree of effort from his cast and crew, never making it easy. “If we could get to a location site without fording a couple of streams and walk through snake-infested areas in the scorching sun, then it wasn’t quite right,” remembered Bogart. Production costs increased, and so did Warner’s frustration with the project. Finally, when Huston ran into some political trouble with a local newspaper, Warner used the situation to pull Huston back to the studio. Rear-projected backdrops were used to complete the majority of scenes in downtown Tampico. By the time production wrapped, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre had cost the studio just under $3 million to complete, and now they weren’t sure how to market it. Warner’s posters made it look like a heroic Western, and the promotional department created treasure maps as handouts. And then there was the issue of Bogart, who had become a charismatic hero in Warner Bros. titles like Casablanca (1942), To Have and Have Not (1944), and The Big Sleep (1944). How would audiences respond to seeing Bogart as someone so despicable as Fred C. Dobbs?

Indeed, Bogart plays one of cinema’s most contemptible, selfish, and paranoid characters. Dobbs is unpleasant and hostile from the film’s first scenes when a lottery boy keeps asking him to purchase a ticket and lowers the price each time, until Dobbs tosses a drink in the child’s face. Of course, he eventually buys the ticket to silence the boy, but only after humiliating him; even worse, the ticket is a winner. Dobbs is a clashing character, at times willing to share his earnings, such as the lottery winnings he shares with Curtin to stake their excursion. Later, Dobbs uses that very fact in a power play, holding his contribution over the heads of his two partners. Dobbs is also competitive and petty, early on boasting about how many bandits he killed during a train raid—though their leader, known as Gold Hat (Alfonso Bedoya), gets away—as though it was important to either Curtin or Howard how many lives each of them took. Self-obsessed, Dobbs desperately wants approval, respect, and to get an edge, perhaps because an edge has long eluded him. When the three strike gold, Dobbs is the first to propose they cut up their findings as they go, as opposed to after the entire dig—to make each man responsible for his cut. And though he claimed $25,000 would be enough to live on, later he calls it “small potatoes.” Soon, he takes to checking his stash in the middle of the night and muttering to himself in fits of paranoia—things like, “Won’t catch me sleeping” and “I’ll let you have it”. Howard, never one to mince words or mutter, tells him, “Got somethin’ up yer nose? Blow it out, it’ll do you good.”

Indeed, Bogart plays one of cinema’s most contemptible, selfish, and paranoid characters. Dobbs is unpleasant and hostile from the film’s first scenes when a lottery boy keeps asking him to purchase a ticket and lowers the price each time, until Dobbs tosses a drink in the child’s face. Of course, he eventually buys the ticket to silence the boy, but only after humiliating him; even worse, the ticket is a winner. Dobbs is a clashing character, at times willing to share his earnings, such as the lottery winnings he shares with Curtin to stake their excursion. Later, Dobbs uses that very fact in a power play, holding his contribution over the heads of his two partners. Dobbs is also competitive and petty, early on boasting about how many bandits he killed during a train raid—though their leader, known as Gold Hat (Alfonso Bedoya), gets away—as though it was important to either Curtin or Howard how many lives each of them took. Self-obsessed, Dobbs desperately wants approval, respect, and to get an edge, perhaps because an edge has long eluded him. When the three strike gold, Dobbs is the first to propose they cut up their findings as they go, as opposed to after the entire dig—to make each man responsible for his cut. And though he claimed $25,000 would be enough to live on, later he calls it “small potatoes.” Soon, he takes to checking his stash in the middle of the night and muttering to himself in fits of paranoia—things like, “Won’t catch me sleeping” and “I’ll let you have it”. Howard, never one to mince words or mutter, tells him, “Got somethin’ up yer nose? Blow it out, it’ll do you good.”

Dobbs’ suspicion begins as petty bickering and grumbling but soon gives way to threats, turning the camp toxic, dangerous even. We might even feel sorry for Dobbs through his descent, except that he remains indefensible and downright pitiless. Consider Dobbs’ quick and cruel logic when a cunning, unwanted stranger named Cody (Bruce Bennett) arrives and demands to become a partner. Cody offers them an alternative he doesn’t think they’ll take, suggesting they can either kill him or allow him to join. If they allow Cody to leave, he could give away the location of their mine—to which they have no official claim. Dobbs demands a vote, and along with Curtin, they have the majority to murder Cody and protect their mine. Fortunately, before they can carry out their frontier murder, Gold Hat and his bandits attack and do the job for them. Their morals have sloped into a cold democratic justification, whereas earlier there was no question as the right thing to do. For example, there’s an early scene in which a cave-in traps Dobbs inside, and Curtin hesitates to carry out a rescue. Leaving Dobbs to die would mean a larger cut, after all. But Curtin’s indecision is brief, and he soon races to rescue his partner without the need for a vote because it’s the right thing to do. Later in the film, Curtin’s sense of moral obligation is rewarded with a bullet.

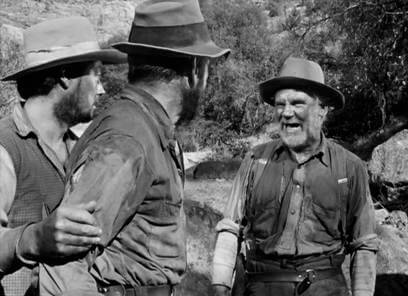

None of this behavior surprises Howard. A scruffy mountain man of immeasurable experience, Howard is brought to life by Walter Huston in a scrappy performance that stands as an archetype for every subsequent old prospector role. He knows every which way it might turn out and doesn’t waste time overthinking the possible outcomes. He speaks plain and says what he means, and he talks so fast that he seems to start the next sentence before he finishes the current one. For the role, the director demanded that his sixty-two-year-old father remove his dentures to play Howard, and so, always a professional, the father obliged his son, saying, “The director is always the father figure on the set, so I suppose.” The actor embodies Howard, his eyes squinted, his scruffy beard and matted hair, his nimble physique, that wild laugh, and that famous jig when they discover gold. Howard becomes more than a mere prospector trope as the story goes on. A group of locals from a nearby village enter their camp one night, asking for help to save a young boy who has fallen into the water and, though breathing, remains unresponsive. Howard agrees to go along and by some wonder saves the boy, like reawakening a newborn into the world. The next day the locals want to honor him in a celebration; he’s forced to leave his share of the gold with Dobbs and Curtin, but he doesn’t seem to mind. He’ll eventually become a wise elder in the village, and he can live a comfortable life being “worshiped for telling people what they want to hear”. Be it gold riches or three meals a day in a small village, it’s all the same to Howard.

None of this behavior surprises Howard. A scruffy mountain man of immeasurable experience, Howard is brought to life by Walter Huston in a scrappy performance that stands as an archetype for every subsequent old prospector role. He knows every which way it might turn out and doesn’t waste time overthinking the possible outcomes. He speaks plain and says what he means, and he talks so fast that he seems to start the next sentence before he finishes the current one. For the role, the director demanded that his sixty-two-year-old father remove his dentures to play Howard, and so, always a professional, the father obliged his son, saying, “The director is always the father figure on the set, so I suppose.” The actor embodies Howard, his eyes squinted, his scruffy beard and matted hair, his nimble physique, that wild laugh, and that famous jig when they discover gold. Howard becomes more than a mere prospector trope as the story goes on. A group of locals from a nearby village enter their camp one night, asking for help to save a young boy who has fallen into the water and, though breathing, remains unresponsive. Howard agrees to go along and by some wonder saves the boy, like reawakening a newborn into the world. The next day the locals want to honor him in a celebration; he’s forced to leave his share of the gold with Dobbs and Curtin, but he doesn’t seem to mind. He’ll eventually become a wise elder in the village, and he can live a comfortable life being “worshiped for telling people what they want to hear”. Be it gold riches or three meals a day in a small village, it’s all the same to Howard.

Tragedy seems too delicate a word to describe what happens after the men resolve to close their camp and part ways; then again, the word “tragedy” has an emotional implication that feels more fateful than the unceremonious way in which Dobbs meets his end. The voice of reason, Howard must remain at the local village and meet his partners several days later, while Dobbs and Curtin travel to Durango with the group’s gold. With Howard gone, it becomes easier for Dobbs to fall prey to madness and feverish suspicion, requiring him to shoot Curtin in an act of preemptive “self-defense”—in other words, attempted murder. Dobbs takes the gold and runs, believing Curtin dead. None of this surprises Howard much after Curtin wanders into the village with a hole in his shoulder. As Howard dresses Curtin’s wound, he calls Dobbs “honest as the next fella,” suggesting his view of humanity is grim, that he believes people are capable of anything. Meanwhile, as Dobbs struggles on the trail with a line of burros, he stops for water and collapses over a putrid watering hole. In his reflection, he sees Gold Hat and several other bandits behind him. Dobbs tries to talk his way out of being cornered, but they want his hides and remain completely oblivious to the sacks of gold strapped to his burros. Within seconds, the bandits behead Dobbs and dump his gold onto the ground, thinking it sand. They take off with his burros and hides. And though they face swift Mexican justice in the following scene, the gold is gone.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre ends with Dobbs dead, while Howard and Curtin laugh at the cruel irony. They have no gold, but Howard will become a revered village elder and Curtin will seek out Cody’s widow on an idyllic fruit farm. The ending contains a poetry worthy of Hemingway’s themes about man’s failure against the natural world and the beauty in our inability to conquer Nature. Still, despite the thematic artistry, Warner protested against the grim ending that leaves Bogart’s character beheaded and his two surviving partners penniless. Nevertheless, after a few positive screenings in 1947, Warner called it “definitely the greatest motion picture we have ever made. It is really one that we have always wished for.” Huston’s once and future proponent James Agee, writing in Time magazine, declared The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is “one of the best things Hollywood has done since it learned to talk; and the movie can take a place, without blushing, among the best ever made… One of the most visually alive and beautiful movies I have ever seen.” Several assessments from the period commended Huston’s production, but the actors justifiably received the highest praise. At the Academy Award ceremony the following year, Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet took home the Best Picture statue; but Walter Huston won for Best Supporting Actor and made sure to thank his son for finding “a good part for your old man”; and John Huston won twice for Best Direction and Best Adapted Screenplay. To the shame of the Academy, Bogart wasn’t even nominated.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre ends with Dobbs dead, while Howard and Curtin laugh at the cruel irony. They have no gold, but Howard will become a revered village elder and Curtin will seek out Cody’s widow on an idyllic fruit farm. The ending contains a poetry worthy of Hemingway’s themes about man’s failure against the natural world and the beauty in our inability to conquer Nature. Still, despite the thematic artistry, Warner protested against the grim ending that leaves Bogart’s character beheaded and his two surviving partners penniless. Nevertheless, after a few positive screenings in 1947, Warner called it “definitely the greatest motion picture we have ever made. It is really one that we have always wished for.” Huston’s once and future proponent James Agee, writing in Time magazine, declared The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is “one of the best things Hollywood has done since it learned to talk; and the movie can take a place, without blushing, among the best ever made… One of the most visually alive and beautiful movies I have ever seen.” Several assessments from the period commended Huston’s production, but the actors justifiably received the highest praise. At the Academy Award ceremony the following year, Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet took home the Best Picture statue; but Walter Huston won for Best Supporting Actor and made sure to thank his son for finding “a good part for your old man”; and John Huston won twice for Best Direction and Best Adapted Screenplay. To the shame of the Academy, Bogart wasn’t even nominated.

More than Huston’s gorgeous locations or thematic fearlessness, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre belongs to its actors and their ability to bring these characters to life. In particular, Bogart and Walter Huston tested their comfort zones and pushed the limits of cinematic characters from the era. After the film’s release, John Huston would direct other actors in some of their finest roles. He teamed with Bogart again on Key Largo (1948) and The African Queen (1951), and the latter film finally earned Bogart his Oscar for Best Actor. He directed Marilyn Monroe in her final performance on The Misfits (1960). And he continued to take on challenging material, or scripts that meant a technically difficult shoot, and he often pursued these pictures solely for the opportunity to travel to exotic locations. He famously wanted to hunt in Africa, so he shot The African Queen in Uganda and throughout the Congo; he went to Morocco for The Man Who Would Be King (1975); and he returned to Mexico for Under the Volcano (1984). Over the years, the director also took various acting roles. In Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), he appeared as crooked landowner Noah Cross. He voiced Gandalf in Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass’ animated adaptations of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth saga, and that distinct voice later shaped Daniel Day Lewis’ iconic performance in There Will Be Blood (2007), which drew major inspiration from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

John Huston, a filmmaker of legendary skill and daring, directs his greatest film with his father as the star, commands an unforgettable performance by his friend and frequent collaborator Humphrey Bogart, and captures the unforgiving yet stunning backdrop of the Mexican wilderness. His story of humanity’s trivial ambitions in the face of Nature seems to find a balance somewhere between irony and fate, although the greater lesson remains how the world at large feels no sense of obligation or sympathy to those who inhabit it. From the perspective that the whole of humankind bends to these forces, Dobbs might seem like a tragic hero who grapples with Nature and his conscience only to lose, except nothing about Bogart’s character is heroic. Instead, Walter Huston’s singular, straightforward quality as Howard remains a noble ideal, as he accepts Nature in all its beauty and perceived cruelty, and rather than try to conquer it out of self-preservation and greed, he partakes with respect and admiration. Howard stands as an extraordinary, Hemingwayan character in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, a tale worthy of Hemingway himself, where weak men fall apart and lose themselves, while those who persevere seem to do so out of their know-how and sheer grit.

John Huston, a filmmaker of legendary skill and daring, directs his greatest film with his father as the star, commands an unforgettable performance by his friend and frequent collaborator Humphrey Bogart, and captures the unforgiving yet stunning backdrop of the Mexican wilderness. His story of humanity’s trivial ambitions in the face of Nature seems to find a balance somewhere between irony and fate, although the greater lesson remains how the world at large feels no sense of obligation or sympathy to those who inhabit it. From the perspective that the whole of humankind bends to these forces, Dobbs might seem like a tragic hero who grapples with Nature and his conscience only to lose, except nothing about Bogart’s character is heroic. Instead, Walter Huston’s singular, straightforward quality as Howard remains a noble ideal, as he accepts Nature in all its beauty and perceived cruelty, and rather than try to conquer it out of self-preservation and greed, he partakes with respect and admiration. Howard stands as an extraordinary, Hemingwayan character in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, a tale worthy of Hemingway himself, where weak men fall apart and lose themselves, while those who persevere seem to do so out of their know-how and sheer grit.

Bibliography:

Huston, John. An Open Book. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980.

Kaminsky, Stuart. John Huston: Maker of Magic. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1978.

Tracy, Tony; Flynn, Roddy. John Huston: Essays on a Restless Director. North Carolina: McFarland, 2010.

There Will Be Blood

There Will Be Blood  Captain Blood

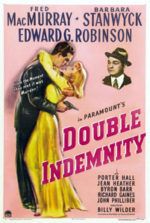

Captain Blood  Double Indemnity

Double Indemnity