The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

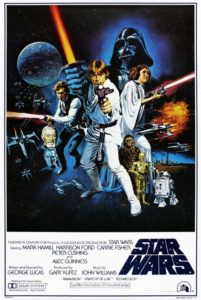

Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope

- Director

- George Lucas

- Cast

- Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Alec Guinness, Peter Cushing, Anthony Daniels, Kenny Baker, Peter Mayhew

- Rated

- PG

- Runtime

- 121 min.

- Release Date

- 05/25/1977

Star Wars belongs on a shortlist of important films that have been so saturated into our minds, so ingrained and present in our everyday culture, that watching the film now is almost an empty experience. Envy those who see it for the first time, especially if they have no prior exposure to the Star Wars phenomenon, if such a person exists. Every iconic scene and character in George Lucas’ 1977 landmark has been recreated as either homage or parody, inspiring countless motion pictures to follow. Every major studio has modeled at least one of their blockbusters on the formula of Star Wars. Alongside The Wizard of Oz or Gone with the Wind, the experience of watching a film like Star Wars today becomes a purely analytical exercise; its emotional core has been worn down to virtual nonexistence by overexposure and Lucas’ subsequent retooling of the film itself. And yet, the original Star Wars remains an undeniable milestone in film history. For better or worse, it shaped the way Hollywood makes movies and how audiences watch them, reducing both to the level of escapism, albeit a fantastic degree of escapism. More significantly, looking back at the way Lucas conceived and executed Star Wars speaks to a cycle of influence, connecting the artists that inspired him to those who continue to draw influence from the Star Wars legacy.

Lucas’ original film came from a plethora of influences, films he loved and admired, from Flash Gordon serials, about a polo player turned intergalactic hero, to Japanese adventures. He expertly recreated those influences into something familiar—for example, Star Wars takes the scrolling text in its opening directly from Flash Gordon serials—but also something incredibly new and formative. Moviegoers lucky enough to have seen Star Wars during its original theatrical run saw something pure. This was before any talk of “Episode IV” or “A New Hope”. Before any CGI critters were digitally implanted into several scenes. Before Greedo shot first. Before Han Solo clumsily stepped over Jabba the Hutt’s cartoon tail. Before a trilogy of prequels lessened everything the 1977 original represented. Even before the two sequels, The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983), deepened the heroic mythology into less an adventure saga than a soapy space melodrama. What has happened to Star Wars since its release could be considered tragic and sad, the rape of great artistry by the artist himself. But how could Lucas have known then what Star Wars would become and how it would affect Hollywood? And if he had known, would he still have made it? Such speculative questions need not be asked in this appreciation of Star Wars. Rather, let’s forget about the consequence of Star Wars—for a while, anyway—and even the plot; instead, let’s consider the film itself and the inspired place from which it was derived.

In many ways, Star Wars is a perfect representation of Lucas himself at that time, his own obsessions and interests. It remains more attuned to the director’s early films, THX 1138 (1971) and American Graffiti (1973), than what followed. Lucas had been developing Star Wars, or something like it, since the early 1970s, when he was inspired to create something like the crudely produced Flash Gordon matinee serials he loved as a boy (just as adventure serials would inspire Raiders of the Lost Ark years later). Although Lucas has long been fascinated by automobiles, machines, and racing, and originally wanted to race cars or become a mechanic, a near-fatal car crash as a teenager led him to a life of study and art. He eventually attended USC’s prestigious film school program and found himself exposed to world cinema and experimental filmmaking. His initial passion for abstract cinema had an undeniable influence on the concept of his short film and later feature-length version of THX 1138. That film takes place in a completely white setting devoid of visible walls or structure, whereas his penchant for science-fiction and comics informed THX 1138‘s conclusion—a man on the run for having fallen in love escapes his oppressive, Orwellian world of white, only to discover he’s been trapped in a subterranean city beneath a post-apocalyptic surface.

In many ways, Star Wars is a perfect representation of Lucas himself at that time, his own obsessions and interests. It remains more attuned to the director’s early films, THX 1138 (1971) and American Graffiti (1973), than what followed. Lucas had been developing Star Wars, or something like it, since the early 1970s, when he was inspired to create something like the crudely produced Flash Gordon matinee serials he loved as a boy (just as adventure serials would inspire Raiders of the Lost Ark years later). Although Lucas has long been fascinated by automobiles, machines, and racing, and originally wanted to race cars or become a mechanic, a near-fatal car crash as a teenager led him to a life of study and art. He eventually attended USC’s prestigious film school program and found himself exposed to world cinema and experimental filmmaking. His initial passion for abstract cinema had an undeniable influence on the concept of his short film and later feature-length version of THX 1138. That film takes place in a completely white setting devoid of visible walls or structure, whereas his penchant for science-fiction and comics informed THX 1138‘s conclusion—a man on the run for having fallen in love escapes his oppressive, Orwellian world of white, only to discover he’s been trapped in a subterranean city beneath a post-apocalyptic surface.

At USC, Lucas discovered the films of Akira Kurosawa, beginning with Seven Samurai (1954). “After that I was completely hooked,” he said in an interview conducted about Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress (1958), a film from which he would borrow several ideas for Star Wars. “It’s really his visual style to me that is so strong and unique,” Lucas admitted. To be sure, Lucas borrows much from the Japanese master to create the powerful visual form of Star Wars, from transitional swipes to Kurosawa’s use of long lenses. Inside the expansive frame of his frequent wide shots, Kurosawa’s characters appear isolated, deep in their environment; the shot from Star Wars where Luke looks at the two moons of Tatooine comes to mind. Lucas’ interests and strengths as an early filmmaker were primarily visual in nature. Many of his short films at the University of Southern California resisted narrative in place of unique visuals and graphics. His love of mechanics transformed into a love of film cameras and how to manipulate them to achieve the look he wanted; he knew what he wanted to see and toiled to achieve that particular look. Since he was still close to his study of Kurosawa, the Japanese filmmaker’s style is evident throughout Star Wars, which, along with incredibly iconographic character and set designs, and more than character depth or sharp dialogue, made the saga memorable.

Though friend Francis Ford Coppola assisted Lucas in his attempt to secure the needed rights to adapt writer and illustrator Alex Raymond’s popular comic strip Flash Gordon in 1971, King Features, owners of the rights, denied the bid as too low. Instead, Lucas resolved to create an original story in the vein of Flash Gordon as part of his deal with United Artists to make American Graffiti. When United Artists registered the title “The Star Wars” in 1971, Lucas had no idea what the film was about—not until he wrapped on American Graffiti did he begin to explore his ideas, such as a dogfight in space inspired by The Dam Busters (1955). Rather than devising plots, he came up with odd names (like Mace Windi, Bink Valor, and Dai Noga) and imagined stories for them, developing an alien mythology. His agent deemed his initial ideas overly complicated, and so Lucas simplified, drawing inspiration from his betters. He had always sought to make a comic book in space, and so he returned to Raymond and other sources for inspiration. Raymond’s comics came from a combination of Buck Rogers, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars novels, and Jules Verne, and Lucas saturated himself in that material. Lucas steeped his screenplay in textual and cinematic homage, expanding much from just Flash Gordon. Elements of Star Wars take influence from Frank Herbert’s Dune series in the details of the desert planet Tatooine and its “spice” product, the depiction of spaceships in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) shaped the Empire’s slow-moving Star Destroyers, and C3PO bears a curious resemblance to Fritz Lang’s iconic robot in Metropolis (1927).

Though friend Francis Ford Coppola assisted Lucas in his attempt to secure the needed rights to adapt writer and illustrator Alex Raymond’s popular comic strip Flash Gordon in 1971, King Features, owners of the rights, denied the bid as too low. Instead, Lucas resolved to create an original story in the vein of Flash Gordon as part of his deal with United Artists to make American Graffiti. When United Artists registered the title “The Star Wars” in 1971, Lucas had no idea what the film was about—not until he wrapped on American Graffiti did he begin to explore his ideas, such as a dogfight in space inspired by The Dam Busters (1955). Rather than devising plots, he came up with odd names (like Mace Windi, Bink Valor, and Dai Noga) and imagined stories for them, developing an alien mythology. His agent deemed his initial ideas overly complicated, and so Lucas simplified, drawing inspiration from his betters. He had always sought to make a comic book in space, and so he returned to Raymond and other sources for inspiration. Raymond’s comics came from a combination of Buck Rogers, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars novels, and Jules Verne, and Lucas saturated himself in that material. Lucas steeped his screenplay in textual and cinematic homage, expanding much from just Flash Gordon. Elements of Star Wars take influence from Frank Herbert’s Dune series in the details of the desert planet Tatooine and its “spice” product, the depiction of spaceships in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) shaped the Empire’s slow-moving Star Destroyers, and C3PO bears a curious resemblance to Fritz Lang’s iconic robot in Metropolis (1927).

But by far, the most significant influence on Lucas was Kurosawa, the Japanese “emperor” of cinema; he was such an influence that Lucas would later personally invest in Kurosawa’s epic Kagemusha (1980). It was not only Kurosawa that inspired Lucas, but Japanese culture as a whole. “Han”, for example, was a popular Japanese name, whereas “Jedi” sounded very much like jidaigeki, the Japanese word for the period films to which Kurosawa was most attributed. The Hidden Fortress inspired Lucas the most, from its plot structure to its character designs. Lucas’ earliest treatments came so close to a remake of Kurosawa’s film that he even considered purchasing the film rights and producing a science-fiction remake. Indeed, the formative influence of The Hidden Fortress on Star Wars cannot be underemphasized; Michael Kaminski’s book The Secret History of Star Wars offers a scene-by-scene comparison, and reviewing it may be the only way to fully appreciate how much Lucas owes to Kurosawa’s film. For example, Lucas borrows early scenes in Star Wars—where C3PO and R2D2 escape an Empire raid, cross a Tatooine desert, are taken as Jawa property, and eventually sold to the hero, Luke Skywalker—from the opening sequences of The Hidden Fortress, which opens with two bickering peasants crossing a landscape wrought by civil war. Eventually, the two peasants come across an experienced general, who devotes himself to protecting a young and impetuous princess, characters Lucas represented with Obi-Wan Kenobi and Princess Leia. Lucas’ visual style also draws heavily from Kurosawa, as discussed. But should one compare The Hidden Fortress and Star Wars back-to-back, the influence would be undeniable. Of course, Kurosawa has his influences too; in particular, he adapted Shakespeare a number of times for Throne of Blood (1957, Macbeth), The Bad Sleep Well (1960, Hamlet), and Ran (1985, King Lear). Perhaps this accounts for why Star Wars resonates with so many, and why many regard its otherwise comic-book stylings as high art, or at least high entertainment.

Lucas toiled over writing Star Wars, which had a number of different titles and characters over several drafts. Many of the character names were abandoned and used later in the prequels, whereas titles like “The Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller” and the even more cumbersome “The Adventures of Luke Starkiller as taken from the Journal of the Whills, Saga I: The Star Wars” were laughable. “I’m not a good writer,” he told an interviewer in 1974. “It’s very, very hard for me. I don’t feel I have a natural talent for it—as opposed to camera, which I could always just do. It was natural.” Perhaps this is why his prequels, often written hastily and without a collaborator, prove so generic and lifeless. He admitted, “I don’t have a natural talent for writing. When I sit down I bleed on the page, and it’s just awful. Writing just doesn’t flow in a creative surge the way other things do.” Though Lucas’ screenplay underwent several drafts and remained ever-changing even into the filming process, the basic story involves simple notions of good and evil, destiny, and myth. In that sense, Star Wars has more in common with a fable than science fiction—in fact, his early college studies focused on anthropology, and how myths and religions form as a result of human culture. These ideas informed his writing process, leading to the mythic nature of his saga and notions of “The Force”. While he wrote, Lucas frequently referenced Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, wherein Campbell expounds his monomyth theory: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Lucas toiled over writing Star Wars, which had a number of different titles and characters over several drafts. Many of the character names were abandoned and used later in the prequels, whereas titles like “The Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller” and the even more cumbersome “The Adventures of Luke Starkiller as taken from the Journal of the Whills, Saga I: The Star Wars” were laughable. “I’m not a good writer,” he told an interviewer in 1974. “It’s very, very hard for me. I don’t feel I have a natural talent for it—as opposed to camera, which I could always just do. It was natural.” Perhaps this is why his prequels, often written hastily and without a collaborator, prove so generic and lifeless. He admitted, “I don’t have a natural talent for writing. When I sit down I bleed on the page, and it’s just awful. Writing just doesn’t flow in a creative surge the way other things do.” Though Lucas’ screenplay underwent several drafts and remained ever-changing even into the filming process, the basic story involves simple notions of good and evil, destiny, and myth. In that sense, Star Wars has more in common with a fable than science fiction—in fact, his early college studies focused on anthropology, and how myths and religions form as a result of human culture. These ideas informed his writing process, leading to the mythic nature of his saga and notions of “The Force”. While he wrote, Lucas frequently referenced Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, wherein Campbell expounds his monomyth theory: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

From Raymond to Kurosawa to Campbell, Star Wars synthesizes archetypical ideas into something archetypal in itself. If the viewer considers Star Wars alone, before the sequels and prequels transformed its purity into an episodic “space opera” driven by soapy extremes (complete with secret family ties revealed, spirit guides, and a black villain who ends up a hero), the film’s pureness conquers classical storytelling in a way its subsequent additions do not. After his family is killed by the evil Empire, young aspiring hero Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) trains to become a member of the lost order of Jedi Knights under the tutelage of old general Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness). Obi-Wan teaches Luke about The Force, a mysterious presence in the universe connecting all things. They team with a couple of rogues, Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew), and attempt to rescue the imprisoned Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) from capture. During their rescue, Luke witnesses his master Obi-Wan cut down by the Emperor’s right hand, Darth Vader (Anthony Prouse, voiced by James Earl Jones). After a narrow escape, the heroes regroup with the Rebellion and launch an attack mission against the Death Star, a base with weapons powerful enough to destroy a planet. With a crucial assist by Han Solo, Luke uses The Force to deliver the final shot against the Death Star, detonating it, and they both become heroes celebrated by the Rebellion in the process. Looking at the broadstrokes of the plot this way, Star Wars couldn’t be any more monomythical unless Campbell himself wrote it. And yet, quite crucially in 1977, Star Wars‘ universality spoke to both mainstream and counter-cultural crowds.

By the late 1960s, the last relics of Hollywood’s Golden Age witnessed a counter-culture takeover with the huge box-office successes of Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1967), and Night of the Living Dead (1968). Strange films began to attract younger viewers and, at the same time, baffle the old studio execs. The studios quickly learned that different was good; different meant teens and young adults, and they meant dollars. Audiences, cynical from the assassination of JFK, the Vietnam War, and eventually Nixon’s resignation, sought out material like Easy Rider (1969) that tore down the romantic conventions of classic architecture. Younger, rebellious generations flocked to the theaters and equally young, independent filmmakers reflected the new generation’s feelings with a slew of youth-oriented titles. It was in this environment that Lucas began writing Star Wars in May of 1973 and, after several drafts and a troubled (if not painful) writing process, at last, delivered the final draft in January of 1976. The plot ideas and characters cut from the final draft of Star Wars, including the idea of “Episode” titles in the vein of Flash Gordon serials, were kept and later incorporated into sequels and prequels. Representative of this New Hollywood band of brash directors, Lucas began pre-production before Twentieth Century Fox even green-lit Star Wars until finally, of course, they agreed to finance and distribute the film without much interest (thus allowing Lucas to incorporate merchandising profits into his contract, forever securing his bankroll).

By the late 1960s, the last relics of Hollywood’s Golden Age witnessed a counter-culture takeover with the huge box-office successes of Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1967), and Night of the Living Dead (1968). Strange films began to attract younger viewers and, at the same time, baffle the old studio execs. The studios quickly learned that different was good; different meant teens and young adults, and they meant dollars. Audiences, cynical from the assassination of JFK, the Vietnam War, and eventually Nixon’s resignation, sought out material like Easy Rider (1969) that tore down the romantic conventions of classic architecture. Younger, rebellious generations flocked to the theaters and equally young, independent filmmakers reflected the new generation’s feelings with a slew of youth-oriented titles. It was in this environment that Lucas began writing Star Wars in May of 1973 and, after several drafts and a troubled (if not painful) writing process, at last, delivered the final draft in January of 1976. The plot ideas and characters cut from the final draft of Star Wars, including the idea of “Episode” titles in the vein of Flash Gordon serials, were kept and later incorporated into sequels and prequels. Representative of this New Hollywood band of brash directors, Lucas began pre-production before Twentieth Century Fox even green-lit Star Wars until finally, of course, they agreed to finance and distribute the film without much interest (thus allowing Lucas to incorporate merchandising profits into his contract, forever securing his bankroll).

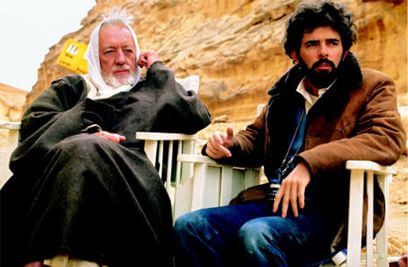

When the production started shooting in Tunisia on March 22, 1976, the director had no idea of the troubles that would follow, which would ultimately influence his decision not to direct The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi himself. Lucas’ trials have been detailed in countless books, most notably J.W. Rinzler’s The Making of Star Wars. In an interview with Rolling Stone after he finished shooting, Lucas said, “I struggled through this movie… This was a big expensive movie and the money was getting wasted and things weren’t coming out right. I was running the corporation. I wasn’t making movies like I’m used to doing.” To be sure, Lucas worked with a tight-knit group of around 40 crew members on THX 1138 and American Graffiti, but he had to oversee nearly 1,000 people for Star Wars. His foreign crew was unreceptive to him as he couldn’t articulate what he wanted due to language barriers, and he felt homesick. He felt the special effects by his company Industrial Light & Magic were imperfect, the robots never functioned correctly, and the practical makeup masks were silly looking. None of it looked the way he saw it in his head, and cinematographer Gil Taylor couldn’t achieve the precise lighting Lucas wanted. Moreover, the editing process was rushed. When he showed an early cut to studio execs and friends like Spielberg and Brian De Palma, everyone except Spielberg was convinced Lucas would barely make back his budget, if not maybe earn enough to justify a sequel. Only Spielberg demonstrated his unique foresight when he told Lucas that he had made an instant classic. Sure enough, Star Wars quickly became one of the highest-grossing films of all time, and one of 1977’s best-reviewed titles. Only a month after its release, Lucas began contemplating a sequel and the studio began demanding it.

Since the Flash Gordon serials from 1936 were essentially an early form of television, designed to get viewers back in their seats for the next chapter, it’s no wonder Lucas developed two sequels to Star Wars, re-released the film in 1981 under the cryptic title Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, and then twenty years later developed three prequels. As suggested earlier, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi disfigure the pure story of Star Wars, but as a trilogy, they remain relatively cohesive (what’s more, Lucas participated only as producer and story contributor in Episodes V and VI; the screenplays and direction were handled by other talent). As time went on and the opportunity cost of not making more Star Wars films loomed, Lucas began experimenting with computer-generated imagery (CGI), popularized by Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park in 1993. By 1997, he re-released the original trilogy back into theaters as “Special Editions” with new edits, absurd digitally animated creatures, and unfinished scenes now completed with CGI and recut into the film, such as an encounter between Han and Jabba the Hutt early in Star Wars. The result offended many otherwise enthusiastic fans and Lucas received many outrageous accusations that he had tampered with moviegoers’ memories and childhood. Nevertheless, the “Special Editions” reinvigorated box-office and merchandising sales for the franchise. Before long, Lucas began work to solely write and direct a prequel trilogy—where special FX were rendered almost completely with CGI, and eventually shot all on digital cameras. Whereas Lucas had once relied on his influences to tell a classical story, now he resolved to invent the later films, writing and all, and most of the stories were cranked out in a matter of months, as opposed to Star Wars‘ three-year labor. (One can’t help but think about his earlier quote, “I’m not a good writer.”)

Since the Flash Gordon serials from 1936 were essentially an early form of television, designed to get viewers back in their seats for the next chapter, it’s no wonder Lucas developed two sequels to Star Wars, re-released the film in 1981 under the cryptic title Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, and then twenty years later developed three prequels. As suggested earlier, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi disfigure the pure story of Star Wars, but as a trilogy, they remain relatively cohesive (what’s more, Lucas participated only as producer and story contributor in Episodes V and VI; the screenplays and direction were handled by other talent). As time went on and the opportunity cost of not making more Star Wars films loomed, Lucas began experimenting with computer-generated imagery (CGI), popularized by Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park in 1993. By 1997, he re-released the original trilogy back into theaters as “Special Editions” with new edits, absurd digitally animated creatures, and unfinished scenes now completed with CGI and recut into the film, such as an encounter between Han and Jabba the Hutt early in Star Wars. The result offended many otherwise enthusiastic fans and Lucas received many outrageous accusations that he had tampered with moviegoers’ memories and childhood. Nevertheless, the “Special Editions” reinvigorated box-office and merchandising sales for the franchise. Before long, Lucas began work to solely write and direct a prequel trilogy—where special FX were rendered almost completely with CGI, and eventually shot all on digital cameras. Whereas Lucas had once relied on his influences to tell a classical story, now he resolved to invent the later films, writing and all, and most of the stories were cranked out in a matter of months, as opposed to Star Wars‘ three-year labor. (One can’t help but think about his earlier quote, “I’m not a good writer.”)

After years of tampering with his original treasure, Lucas has made the pleasures of Star Wars dissipate, its purity damaged by CGI goofiness, and its association with the creatively disastrous prequels and even the sequels distance Star Wars from Campbell’s monomyth. To enjoy watching Star Wars today requires a certain kind of viewer; specifically, not a modernist. Viewers in our post-modern meta-culture, unconcerned by what has become of Star Wars since its release, can undoubtedly watch the film and ignore the disappointing additions that followed, and still recognize moments of purity in its adventure. Meanwhile, the phenomenon and subculture created by Star Wars rarely pay attention to how Lucas culled ideas, mainly from Flash Gordon and The Hidden Fortress, and repurposed them for Star Wars. Enthusiasts use hyperbolic statements and declare the film’s originality and singularity within the cinematic realm, ignoring how Lucas harvested the majority of his ideas from elsewhere in appreciation of how excellent a synthesis the eventual film proves to be. But Star Wars is not a great film because it does something no one had done before; rather, it remains great because Lucas reshaped his passions into something that at once transcended and embraced his influences. And as reformatting established ideas goes, Lucas does it exceptionally well in his franchise’s first release.

Star Wars may represent a compendium of influences whose sources range from the lowest possible quality serials to the highest order of international cinema, but its genius remains a deceptive and simple distillation of basic motifs that have been engaging audiences for centuries. Lucas created something that uses those motifs to glorious effect. Just as Chaucer, Plutarch, and Virgil inspired Shakespeare, Shakespeare inspired Kurosawa, and Kurosawa inspired Lucas. Today, filmmakers from the Wachowski siblings to Joss Whedon, and virtually every science-fiction effort released since 1977, owe some level of gratitude to Star Wars and George Lucas, thus representing an ongoing cycle of influence. But because Star Wars no longer exists in its 1977 form, cinéastes, namely those fortunate enough to see the film during its original theatrical run, are left only with memories and nostalgia. And while the film’s once-brilliant purity has since been discolored by the surrounding, and certainly eclipsing franchise phenomenon, if audiences can disregard the not inconsiderable baggage attached to Star Wars, they will find something pure that is derived from a place of passion and enthusiasm. How sad that Lucas’ passion and enthusiasm, and most definitely his purity of artistic application, waned in the subsequent years. But for a brief moment in time, Star Wars represented a young artist embracing his inspiration to wonderful effect, and what resulted was something that rose above a product of mere influence and became something timelessly innovative.

Star Wars may represent a compendium of influences whose sources range from the lowest possible quality serials to the highest order of international cinema, but its genius remains a deceptive and simple distillation of basic motifs that have been engaging audiences for centuries. Lucas created something that uses those motifs to glorious effect. Just as Chaucer, Plutarch, and Virgil inspired Shakespeare, Shakespeare inspired Kurosawa, and Kurosawa inspired Lucas. Today, filmmakers from the Wachowski siblings to Joss Whedon, and virtually every science-fiction effort released since 1977, owe some level of gratitude to Star Wars and George Lucas, thus representing an ongoing cycle of influence. But because Star Wars no longer exists in its 1977 form, cinéastes, namely those fortunate enough to see the film during its original theatrical run, are left only with memories and nostalgia. And while the film’s once-brilliant purity has since been discolored by the surrounding, and certainly eclipsing franchise phenomenon, if audiences can disregard the not inconsiderable baggage attached to Star Wars, they will find something pure that is derived from a place of passion and enthusiasm. How sad that Lucas’ passion and enthusiasm, and most definitely his purity of artistic application, waned in the subsequent years. But for a brief moment in time, Star Wars represented a young artist embracing his inspiration to wonderful effect, and what resulted was something that rose above a product of mere influence and became something timelessly innovative.

Bibliography:

Bailey, T. J. Devising a Dream: A Book of Star Wars Facts and Production Timeline. Louisville, KY: Wasteland Press, 2005.

Baxter, John. Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas (1st ed.). New York: William Morrow, 1999.

Bouzereau, Laurent. Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays. New York: Del Rey, 1997.

Brooker, Will. Star Wars. BFI Film Classics. London: BFI, 2009.

Hearn, Marcus. The Cinema of George Lucas. New York: ABRAMS Books, 2005.

Kaminski, Michael. The Secret History of Star Wars: The Art of Storytelling and the Making of a Modern Epic. Kingston, Ont.: Legacy Books Press, 2008.

Rinzler, J.W. The Making of Star Wars. LucasBooks, 2007.

Sansweet, Stephen (1992). Star Wars: From Concept to Screen to Collectible. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back

Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back  Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi

Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi  Ready Player One

Ready Player One