The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

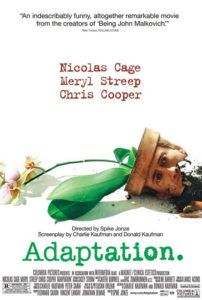

Adaptation.

- Director

- Spike Jonze

- Cast

- Nicolas Cage, Meryl Streep, Chris Cooper, Brian Cox, Tilda Swinton

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 114 min.

- Release Date

- 12/06/2002

After selling his wildly original script for Being John Malkovich, screenwriter Charlie Kaufman lands a job to adapt Susan Orlean’s book The Orchid Thief, an expansion of her article published in The New Yorker in 1995. Her best-seller could have made a great documentary about flowers; it charts the long history of orchid enthusiasts willing to risk their lives for rare specimens, and the latest of these men, John Laroche, is an eccentric Florida orchid farmer and con artist who employs Seminoles to poach rare orchids from protected lands. In the book, Orlean witnesses Laroche’s true passion for flowers and longs to feel something similar in her own life. When faced with translating Orlean’s meandering prose (“New Yorker shit”) to film, Kaufman agonizes over how to penetrate his subject, even while he finds her book endlessly fascinating and identifies with her longing to feel passionate about something. The problem is, Orlean’s book “about flowers” has no plot. In a stroke of genius egomania, Kaufman resolves to incorporate himself into his script, making his screen story about the process of adaptation itself. By fulfilling his own needs as an artist, he captures the essence of Orlean’s novel.

The above paragraph is both a brief background and a plot description to director Spike Jonze’s 2002 film Adaptation., the second collaboration between Jonze and Kaufman after 1999’s Being John Malkovich. This ceaselessly clever, brilliantly mind-bending film taps into the intangible spirit of Orlean’s book by involving the viewer in Kaufman’s painstaking translation to the screen. In the film, Kaufman’s story is told from the perspective of a screenwriter named Charlie Kaufman, played by Nicolas Cage in a career-best, Oscar-nominated performance. Charlie suffers from writer’s block in his efforts to put something original, intelligent, and evocative to paper. At the same time, his uncomplicated, identical twin brother, the fictional Donald (also Cage), follows a banal Hollywood formula to the letter in his first script and achieves outrageous commercial success. By assigning a lead role for himself in his film, and another mirror-image role to signify his worst fears of selling out, Kaufman works through his flooding doubts and neuroses in his art by mutually embracing and transcending Orlean’s source material. More than any other screenwriter working today, Kaufman places himself into his work and becomes a rare example of a writer-auteur, a designation traditionally reserved for film directors.

This is not to discount Spike Jonze, a visual wunderkind and forerunner of the so-called “American New Wave” of modern filmmakers in the 1990s alongside David O. Russell (I Heart Huckabees), Wes Anderson (Rushmore), and Richard Linklater (A Scanner Darkly). A former skateboarding photographer and filmmaker, Jonze began as a premier music video director in the ‘90s, assembling creative shorts for the Beastie Boys (“Sabotage”), R.E.M. (“Crush With Eyeliner”), and Björk (“Oh, So Quiet”). His work in commercials was just as inventive, turning in pieces for Coca-Cola and Nike. His famous Levi’s jeans ad featured an accident victim carted into an emergency room, only to have the hospital’s staff burst into a version of Soft Cell’s cover of “Tainted Love.” Jonze’s filmography—including Where the Wild Things Are (2009), an adaptation of the late Maurice Sendak’s beloved children’s book—is defined by his uniquely inspired penchant for surreality. And that’s exactly what was needed to bring Kaufman’s work to the screen. Only a selfless director could step aside to embrace his writer’s voice fully, and only Jonze could look underneath Kaufman’s initial layer of introverted, narcissistic self-hatred to find the writer’s equally present poignancy and meaning, the profundity of which always manages to outperform even Jonze’s level of directorial style.

This is not to discount Spike Jonze, a visual wunderkind and forerunner of the so-called “American New Wave” of modern filmmakers in the 1990s alongside David O. Russell (I Heart Huckabees), Wes Anderson (Rushmore), and Richard Linklater (A Scanner Darkly). A former skateboarding photographer and filmmaker, Jonze began as a premier music video director in the ‘90s, assembling creative shorts for the Beastie Boys (“Sabotage”), R.E.M. (“Crush With Eyeliner”), and Björk (“Oh, So Quiet”). His work in commercials was just as inventive, turning in pieces for Coca-Cola and Nike. His famous Levi’s jeans ad featured an accident victim carted into an emergency room, only to have the hospital’s staff burst into a version of Soft Cell’s cover of “Tainted Love.” Jonze’s filmography—including Where the Wild Things Are (2009), an adaptation of the late Maurice Sendak’s beloved children’s book—is defined by his uniquely inspired penchant for surreality. And that’s exactly what was needed to bring Kaufman’s work to the screen. Only a selfless director could step aside to embrace his writer’s voice fully, and only Jonze could look underneath Kaufman’s initial layer of introverted, narcissistic self-hatred to find the writer’s equally present poignancy and meaning, the profundity of which always manages to outperform even Jonze’s level of directorial style.

Born in New York in 1958, Kaufman grew up an only child in Connecticut. His early life consisted of a normal suburban upbringing. He did not excel in school nor give his parents any cause to believe he would be extraordinary. He briefly attended Boston University and later studied cinema at NYU Film School, developing tastes for theater and intellectual reading. After graduating, he worked sporadically for National Lampoon magazine and Minneapolis’ Star Tribune newspaper. Then, in 1991, he moved to Hollywood, where he found work writing for television shows like Chris Elliot’s Get a Life! (1991-92) and Dana Carvey’s short-lived sketch comedy show, among others. In 1999, when Kaufman ventured into the mind of intense character actor John Malkovich, his original and comically surreal script made him an overnight star and one of the most talked-about writers in Hollywood. His subsequent scripts for Human Nature (2001) and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2003) were put to film by directors Michel Gondry and George Clooney, respectively, and were modest successes. In 2004, Kaufman received a Best Original Screenplay Oscar for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, a Philip K. Dick-infused romance also directed by Gondry. Finally, in 2010, Kaufman became a full-fledged auteur when he made his debut as writer-director of Synecdoche, New York, a film sharing in Adaptation.’s self-reflectivity but perhaps not its joyous virtuosity.

Kaufman’s films are surrealistic in the traditional sense, reminiscent of Luis Buñuel in that everyone onscreen accepts their odd world no matter how strange. His characters may express their bemusement, but they embrace whatever Kaufman throws at them and even eventually seek to exploit it. In Being John Malkovich, when John Cusack’s puppeteer Craig Schwartz confesses to Catherine Keener his discovery of a portal into John Malkovich’s head, rather than fascination and study, they immediately abuse their finding by selling tickets. Human Nature finds Rhys Ifans’ raised-by-wolves protagonist using his status as a victim of modern science to convince Congress how corruptive of Nature humanity has become, even though he himself has become a willingly corrupted member of the human race. Each work is funny, philosophical, Kafkaesque, incredibly imaginative, and certainly post-modern. When you first see a Charlie Kaufman film, you’ve never seen anything else like it. He explores fantastical ideas and scenarios, yet he finds real characters harboring genuine emotions to populate them. Although, his characters will never find redemption through love or romance; more often, they find it through artistic self-understanding or their own acceptance that the universe is an unfair and cruel place. Despite Kaufman’s employment of fantasticality, his films contain a surprising amount of truth.

In Adaptation.’s opening scenes, Charlie’s producer, Valerie (Tilda Swinton), commends him on his inventive Being John Malkovich script and wants to hear his thoughts on Orlean’s book. Sweaty and nervous in a casual business lunch with a woman to whom he’s attracted, Charlie mutters his way through a speech about keeping true to Orlean’s text when Valerie suggests he should write-in Orlean and Laroche falling in love. “I don’t want to cram in sex or guns or car chases, you know… Or characters, you know, learning profound life lessons, or growing, or coming to like each other, or overcoming obstacles to succeed in the end… I feel very strongly about this.” She concedes to the writer’s confused vision, and Charlie returns home to sit in front of his typewriter. An inner dialogue takes over as Charlie debates with himself about how to start. Should he have a coffee first? He should write something first, then reward himself with coffee. He should eat a muffin. Perhaps he should start at the dawn of time, 4 billion and forty years ago. Banana nut is a good muffin. Inner deliberations such as this are familiar and painfully recognizable to any writer.

Overweight, balding, introverted, self-deprecating, and tremendously intelligent, Charlie recalls Woody Allen’s recurrent persona of a talented and lovable loser. The major difference between Allen’s persona and Kaufman’s is how low Kaufman is willing to take his protagonists, while Allen’s losers rarely have trouble finding lovers and often couple with beautiful actresses (Diane Keaton, Mia Farrow, Dianne Wiest, etc.). If Charlie’s character represents an uncompromising artistic ideal, then his twin brother Donald represents Kaufman’s fear of “going Hollywood.” But ignorance is also bliss. Donald’s blindly positive attitude lands him a cute girlfriend (Maggie Gyllenhaal), favor among the cast of Being John Malkovich (many of whom appear in cameo), respect in the “industry,” and a huge payday for his cornball script. Meanwhile, Charlie does not have the confidence to pursue his interested would-be girlfriend Amelia (Cara Seymour). Cage delivers marvelous dual performances as the twins, defining each role with carefully nuanced body language and speech patterns so that even though his slouched stutterer Charlie and his always wide-eyed Donald look identical, the audience never has trouble telling them apart.

Before Charlie finds a way to start his script, Donald, who lives with Charlie, interrupts him. Donald announces plans to write his own script, a predictable psychological thriller called The 3, about a serial killer with multiple personality disorder. Charlie declares the idea is a cliché wrapped in an overused plot device, but he does not have the energy to explain to Donald why. And so, Donald proceeds, relying heavily on advice given during a seminar by Robert McKee (Brian Cox) and McKee’s ever-present Screenwriting 101 book Story: Substance, Structure, Style and The Principles of Screenwriting—an actual book used by novice screenwriters. McKee’s conventional how-to guide deconstructs classics like Casablanca, and through them, elucidates a very broad cinematic technique to screen storytelling. McKee argues against voiceover, praises the use of a recurring song (think “As Time Goes By”), condemns deus ex machina, and lauds characters who learn profound life lessons—most being ideas to which Charlie is absolutely opposed. Following standardized formulas is not what Charlie does. Moreover, Orlean’s novel does not follow such set structural motifs either, so why should Charlie in his adaptation? As his deadline approaches and his writer’s block endures, however, Charlie finds himself tempted to employ McKee’s principles just to finish the script; he even takes McKee’s seminar and seeks out his counsel. McKee tells Charlie, “Wow them in the end, and you have a hit.”

As Charlie bemoans his screenplay’s non-progress, he reads passages from The Orchid Thief in awe of their beauty, even as he struggles to imagine how such passages will play on film. We see them visualized in Charlie’s head, or perhaps Kaufman’s, as Susan Orlean (Meryl Streep) engages Laroche (Chris Cooper) for a New Yorker interview and finds this unlikely man with no front teeth and a massive ego somehow oddly charming. Using this clever device, Kaufman’s script injects whole segments of Orlean’s book into Adaptation., wherein Orlean streams her thoughts on the beauty of orchids and perplexities of Laroche. But Kaufman does not stop there; he transforms Orlean and Laroche into characters who twist and turn in ways that would make McKee (and Valerie) proud. Just as Charlie’s writer’s block has reached its limit, he wants to seek out Orlean for advice but doesn’t have the confidence to approach her. Donald volunteers to go instead, pretending to be his brother. In time, the brothers begin to spy on Orlean and find a woman bored with her routine New York City intellectual circle. Orlean finds an escape through Laroche, who sees her as needy but doesn’t hesitate when the opportunity arises to bed her. Of course, Kaufman has introduced an affair to juice up his story, just as he introduces a hilarious notion that Laroche harvests a rare Ghost Orchid for its hallucinogenic properties or Laroche’s sudden interest in the lucrative internet pornography business. In these scenes, we witness the incredible range of Streep, whose performance takes her from a reserved intellectual and discerning interviewer to a giggling drug user, from an illicit lover to a desperate murderer. Opposite her, Cooper’s Oscar-winning performance is singular in its layered idiosyncrasies.

As Charlie bemoans his screenplay’s non-progress, he reads passages from The Orchid Thief in awe of their beauty, even as he struggles to imagine how such passages will play on film. We see them visualized in Charlie’s head, or perhaps Kaufman’s, as Susan Orlean (Meryl Streep) engages Laroche (Chris Cooper) for a New Yorker interview and finds this unlikely man with no front teeth and a massive ego somehow oddly charming. Using this clever device, Kaufman’s script injects whole segments of Orlean’s book into Adaptation., wherein Orlean streams her thoughts on the beauty of orchids and perplexities of Laroche. But Kaufman does not stop there; he transforms Orlean and Laroche into characters who twist and turn in ways that would make McKee (and Valerie) proud. Just as Charlie’s writer’s block has reached its limit, he wants to seek out Orlean for advice but doesn’t have the confidence to approach her. Donald volunteers to go instead, pretending to be his brother. In time, the brothers begin to spy on Orlean and find a woman bored with her routine New York City intellectual circle. Orlean finds an escape through Laroche, who sees her as needy but doesn’t hesitate when the opportunity arises to bed her. Of course, Kaufman has introduced an affair to juice up his story, just as he introduces a hilarious notion that Laroche harvests a rare Ghost Orchid for its hallucinogenic properties or Laroche’s sudden interest in the lucrative internet pornography business. In these scenes, we witness the incredible range of Streep, whose performance takes her from a reserved intellectual and discerning interviewer to a giggling drug user, from an illicit lover to a desperate murderer. Opposite her, Cooper’s Oscar-winning performance is singular in its layered idiosyncrasies.

In Adaptation.’s third act “dénouement,” as Donald calls it, Kaufman’s script turns on itself and becomes, knowingly, a product of McKee-brand conventionalism, breaking not only Kaufman’s rules but devolving into a situation wherein his use of deus ex machina becomes a hilariously ironic choice. This is done in the most self-aware of ways—a series of artistic compromises that gradually reveal themselves in Kaufman’s story. Following McKee’s advice, Kaufman introduces a musical theme with The Turtles’ “So Happy Together” sung between Charlie and Donald, who soon discover Orlean and Laroche carrying on together. When Orlean realizes her affair has been revealed, she wants the brothers dead. Laroche hesitates but then goes along with her because his character must to keep the plot moving. There is a chase, a sudden car crash in which Donald dies, and a tender moment when Charlie sings “So Happy Together” to his fading brother. There’s even a deus ex machina in the form of an alligator that attacks Laroche. Of course, this is an intentionally obvious manipulation of the audience, and Kaufman’s tongue-in-cheek way of “wowing” us in the end. These final scenes commit all of those artistic crimes both Kaufman and Charlie were so determined to avoid, even if in this context they do not feel like conventions, but rather Kaufman illustrating how absurd such conventions are.

There is much to keep track of in Adaptation.: Charlie and the process of writing a screenplay, Charlie’s failing personal life and interactions with Donald, sections from The Orchid Thief as read by Charlie, and other passages read from Orlean’s perspective (as imagined and embellished by both Kaufman and Charlie), and visions of a potential film of The Orchid Thief conceived by Charlie. All the while, we must be aware of Kaufman’s voice as he alternates between characters and points of view. As he does with Charlie, Kaufman’s frequent artist characters see themselves clearly enough that, in their dissatisfaction, they create alternate and fantastic realities through their art: Kaufman created Charlie and Donald and their whimsical adventures in the third act; Charlie embraces those adventures in his own script after Donald’s death; in Being John Malkovich, Schwartz acts out his fantasies through his puppet theater and by living in Malkovich; Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Caden Cotard in Synecdoche, New York recreates his entire life on a vast soundstage, accepting life’s lack of meaning only after it becomes an artistic creation. Still, Kaufman’s ongoing series of confessionals about the artistic process—whether from the perspective of puppeteers or screenwriters or theater directors or Darwinians—includes a combination of fiction and real life.

Consider Kaufman’s creative license within his treatment of real people, like Susan Orlean and John Laroche. Both of them must have signed off on Kaufman’s complete creative freedom long before filming began. Any notion of Orlean’s affair with Laroche or their Ghost Orchid drug-running conspiracy is a complete fabrication on Kaufman’s part, explored only to acknowledge the absurdity of Valerie’s suggestion and our affection for Hollywoodized stories. Other characters appear as themselves, such as cameos by John Malkovich, John Cusack, and Catherine Keener, while others still are pure invention on Kaufman’s part—Donald, for instance. Kaufman embraces a practice where authors blend fiction and autobiography into whimsical, self-indulgent, head-spinning delight. Among other films about the writing process like Sunset Boulevard (1950), Barton Fink (1991), Naked Lunch (1991), and Deconstructing Harry (1997), only Adaptation. dwells so on the actual practice of writing, technique, and a severe preoccupation with what authorship means.

The title Adaptation., then, becomes an exceptionally loaded pun, referring to a) Kaufman’s process of reworking Orlean’s book into script form, b) the Darwinian process of involuntary change to one’s surroundings that fascinates Orlean and Laroche, and c) a method through which Kaufman’s characters from Charlie to Orlean reshape their lives by putting themselves into something or someone else. What remains so engaging about Adaptation. is how Kaufman incorporates the artistic ideals of both personalities, Charlie and Donald, into the overall film. And though Kaufman uses Donald’s cherished Hollywood formula, they are used sardonically, if not facetiously. Never once does the film itself feel as though Kaufman has compromised his artistic integrity. As a result, Kaufman’s script comes from both identities, and so both Charlie Kaufman and his fictional brother Donald Kaufman received credit for the film’s screenplay. A product of fantasy, truth, reality, non-fiction, and sheer artistic bravado, this film is the resounding demonstration as to why Kaufman remains a singular auteur screenwriter whose inability to escape his own artistic influence compels his work.

Bibliography:

Hill, Derek. Charlie Kaufman and Hollywood’s Merry Band of Pranksters, Fabulists and Dreamers. Kamera, 2008.

LaRocca, David. The Philosophy of Charlie Kaufman. The University of Kentucky Press, 2011.

Anomalisa

Anomalisa  Synecdoche, New York

Synecdoche, New York  Crimes and Misdemeanors

Crimes and Misdemeanors